Upper West Side

Upper West Side | |

|---|---|

The Upper West Side and Central Park as seen from Top of the Rock observatory at Rockefeller Center. In the background to the west are the Hudson River and the George Washington Bridge. | |

| Nickname: UWS | |

Location in New York City | |

| Coordinates: 40°47′13″N 73°58′30″W / 40.787°N 73.975°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | New York City |

| Borough | Manhattan |

| Community District | Manhattan 7[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 5 km2 (1.9 sq mi) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

• Total | 214,744 |

| • Density | 44,000/km2 (110,000/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • White | 67.4% |

| • Black | 7.6 |

| • Asian | 7.6 |

| • Others | 17.4 |

| Economics | |

| • Median income | $121,032 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 10023, 10024, 10025, 10069 |

| Area code | 212, 332, 646, and 917 |

The Upper West Side (UWS) is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Central Park on the east, the Hudson River on the west, West 59th Street to the south, and West 110th Street to the north. The Upper West Side is adjacent to the neighborhoods of Hell's Kitchen to the south, Columbus Circle to the southeast, and Morningside Heights to the north.[3]

Like the Upper East Side opposite Central Park, the Upper West Side is an affluent, primarily residential area with many of its residents working in commercial areas of Midtown and Lower Manhattan. Similarly to the Museum Mile district on the Upper East Side, the Upper West Side is considered one of Manhattan's cultural and intellectual hubs, with Columbia University and Barnard College located just to the north of the neighborhood, the American Museum of Natural History located near its center, the New York Institute of Technology in the Columbus Circle proximity and Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts and Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School located at the south end.

The Upper West Side is part of Manhattan Community District 7, and its primary ZIP Codes are 10023, 10024, 10025, and 10069.[1] It is patrolled by the 20th and 24th Precincts of the New York City Police Department.

Geography

[edit]

The Upper West Side is bounded on the south by 59th Street, Central Park to the east, the Hudson River to the west, and 110th Street to the north.[4] The area north of West 96th Street and east of Broadway is also identified as Manhattan Valley. The overlapping area west of Amsterdam Avenue to Riverside Park was once known as the Bloomingdale District.

From west to east, the avenues of the Upper West Side are Riverside Drive, West End Avenue (11th Avenue), Broadway, Amsterdam Avenue (10th Avenue), Columbus Avenue (9th Avenue), and Central Park West (8th Avenue). The 66-block stretch of Broadway forms the spine of the neighborhood and runs diagonally north–south across the other avenues at the south end of the neighborhood; above 78th Street Broadway runs north parallel to the other avenues. Broadway enters the neighborhood at its juncture with Central Park West at Columbus Circle (59th Street), crosses Columbus Avenue at Lincoln Square (65th Street), Amsterdam Avenue at Verdi Square (71st Street), and then merges with West End Avenue at Straus Park (aka Bloomingdale Square, at 107th Street).

Traditionally the neighborhood ranged from the former village of Harsenville, centered on the old Bloomingdale Road (now Broadway) and 65th Street, west to the railroad yards along the Hudson, then north to 110th Street, where the ground rises to Morningside Heights. With the construction of Lincoln Center, its name, though perhaps not the reality, was stretched south to 58th Street. With the arrival of the corporate headquarters and expensive condos of the Time Warner Center at Columbus Circle, and the Riverside South apartment complex built by Donald Trump, the area from 58th Street to 65th Street is increasingly referred to as Lincoln Square by realtors who acknowledge a different tone and ambiance than that typically associated with the Upper West Side. This is a reversion to the neighborhood's historical name.

History

[edit]Native American and colonial use

[edit]

The long high bluff above useful sandy coves along the North River was little used or traversed by the Lenape people.[5] A combination of the stream valleys, such as that in which 96th Street runs, and wetlands to the northeast and east, may have protected a portion of the Upper West Side from the Lenape's controlled burns;[6] lack of periodic ground fires results in a denser understory and more fire-intolerant trees, such as American Beech.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, the Upper West Side-to-be contained some of colonial New York's most ambitious houses, spaced along Bloomingdale Road.[7] It became increasingly infilled with smaller, more suburban villas in the first half of the nineteenth century, and in the middle of the century, parts had become decidedly lower class.

Bloomingdale District

[edit]The name "Bloomingdale District" was used to refer to a part of the Upper West Side – the present-day Manhattan Valley neighborhood – located between 96th and 110th Streets and bounded on the east by Amsterdam Avenue and on the west by Riverside Drive, Riverside Park, and the Hudson River.

Its name was a derivation of the description given to the area by Dutch settlers to New Netherland, likely from Bloemendaal, a town in the tulip region.[8] The name was Anglicized to "Bloomingdale" or "the Bloomingdale District", covering the west side of Manhattan from about 23rd Street up to the Hollow Way (modern 125th Street). It consisted of farms and villages along a road (regularized in 1703) known as the Bloomingdale Road. Bloomingdale Road was renamed The Boulevard in 1868, as the farms and villages were divided into building lots and absorbed into the city.[9] By the 18th century it contained numerous farms and country residences of many of the city's well-off, a major parcel of which was the Apthorp Farm. The main artery of this area was the Bloomingdale Road, which began north of where Broadway and the Bowery Lane (now Fourth Avenue) join (at modern Union Square) and wended its way northward up to about modern 116th Street in Morningside Heights, where the road further north was known as the Kingsbridge Road. Within the confines of the modern-day Upper West Side, the road passed through areas known as Harsenville,[10] Strycker's Bay, and Bloomingdale Village.

With the building of the Croton Aqueduct passing down the area between present day Amsterdam Avenue and Columbus Avenue in 1838–42, the northern reaches of the district became divided into Manhattan Valley to the east of the aqueduct and Bloomingdale to the west. Bloomingdale, in the latter half of the 19th century, was the name of a village that occupied the area just south of 110th Street.[11]

Late 19th-century development

[edit]Much of the riverfront of the Upper West Side was a shipping, transportation, and manufacturing corridor. The Hudson River Railroad line right-of-way was granted in the late 1830s to connect New York City to Albany, and soon ran along the riverbank. One major non-industrial development, the creation of Central Park in the 1850s and '60s, caused many squatters to move their shacks into the Upper West Side. Parts of the neighborhood became a ragtag collection of squatters' housing, boarding houses, and rowdy taverns.

As this development occurred, the old name of Bloomingdale Road was being chopped away and the name Broadway was progressively applied further northward to include what had been lower Bloomingdale Road. In 1868, the city began straightening and grading the section of the Bloomingdale Road from Harsenville north, and it became known as "Western Boulevard" or "The Boulevard". It retained that name until the end of the century, when the name Broadway finally supplanted it.

Development of the neighborhood lagged even while Central Park was being laid out in the 1860s and '70s, then was stymied by the Panic of 1873. Things turned around with the introduction of the Ninth Avenue elevated in the 1870s along Ninth Avenue (renamed Columbus Avenue in 1890), and with Columbia University's relocation to Morningside Heights in the 1890s, using lands once held by the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum.[12]

Riverside Park was conceived in 1866 and formally approved by the state legislature through the efforts of city parks commissioner Andrew Haswell Green. The first segment of park was acquired through condemnation in 1872, and construction soon began following a design created by the firm of Frederick Law Olmsted, who also designed the adjacent, gracefully curving Riverside Drive. In 1937, under the administration of commissioner Robert Moses, 132 acres (0.53 km2) of land were added to the park, primarily by creating a promenade that covered the tracks of the Hudson River Railroad. Moses, working with landscape architect Gilmore D. Clarke also added playgrounds, and distinctive stonework and the 79th Street Boat Basin, but also cut pedestrians off from direct access to most of the riverfront by building the Henry Hudson Parkway by the river's edge. According to Robert Caro's book on Moses, The Power Broker, Riverside Park was designed with most of the amenities located in predominantly white neighborhoods, with the neighborhoods closer to Harlem getting shorter shrift.[13] Riverside Park, like Central Park, underwent a revival late in the 20th century, largely through the efforts of the Riverside Park Fund, a citizen's group. Largely through their efforts and the support of the city, much of the park has been improved. The Hudson River Greenway along the river-edge of the park is a common route for pedestrians and bicyclists; an extension to the park's greenway runs between 83rd and 91st Streets on a promenade in the river itself.[14]

Early 20th century

[edit]Subway expansion

[edit]1868 saw the opening of the now demolished IRT Ninth Avenue Line – the city's first elevated railway – which opened in the decade following the American Civil War. The Upper West Side experienced a building boom from 1885 to 1910, thanks in large part to the 1904 opening of the city's first subway line, which comprised, in part, what is now a portion of the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line, with subway stations at 59th, 66th, 72nd, 79th, 86th, 91st, 96th, 103rd, 110th, 116th, and 125th Streets.

This further stimulated residential development of the area. The stately tall apartment blocks on West End Avenue and the townhouses on the streets between Amsterdam Avenue and Riverside Drive, which contribute to the character of the area, were all constructed during the pre-depression years of the twentieth century. A revolution in building techniques, the low cost of land relative to lower Manhattan, the arrival of the subway, and the popularization of the formerly expensive elevator made it possible to construct large apartment buildings for the middle classes. The large scale and style of these buildings is one reason why the neighborhood has remained largely unchanged into the twenty-first century.[11]

The neighborhood changed from the 1930s to the 1950s. In 1932, the IND Eighth Avenue Line opened under Central Park West.[15] In 1940, the elevated IRT Ninth Avenue Line over Columbus Avenue closed.[16] Immigrants from Eastern Europe and the Caribbean moved in during the '50s and the '60s.[17] The Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts opened in the 1960s.[18] The early 20th century marked the beginning of a significant Jewish presence on the Upper West Side. By 1930, Jewish residents constituted approximately one-third of the population living between West 79th and West 110th Streets, from Broadway to the Hudson River. [19]

Enclaves

[edit]In the 1900s, the area south of 67th Street was heavily populated by African-Americans and supposedly gained its nickname of "San Juan Hill" in commemoration of African-American soldiers who were a major part of Theodore Roosevelt's assault on Cuba's San Juan Hill in the Spanish–American War. By 1960, it was a rough neighborhood of tenement housing, the demolition of which was delayed to allow for exterior shots in the film musical West Side Story. Thereafter, urban renewal brought the construction of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts and Lincoln Towers apartments during 1962–1968.

The Upper West Side is a significant Jewish neighborhood, populated with both German Jews who moved in at the turn of last century, and Jewish refugees escaping Hitler's Europe in the 1930s. Today the area between 85th Street and 100th Street is home to the largest community of young Modern Orthodox singles outside of Israel.[20] However, the Upper West Side also features a substantial number of non-Orthodox Jews. A number of major synagogues are located in the neighborhood, including the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States, Shearith Israel; New York's second-oldest and the third-oldest Ashkenazi synagogue, B'nai Jeshurun; Rodeph Sholom; the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue; and numerous others such as the Jewish Center, and West Side Institutional.

Late 20th-century urban renewal

[edit]

From the post-WWII years until the AIDS epidemic, the neighborhood, especially below 86th Street, had a substantial gay population. As the neighborhood had deteriorated, it was affordable to working class gay men, and those just arriving in the city and looking for their first white collar jobs. Its ethnically mixed gay population, mostly Hispanic and white, with a mixture of income levels and occupations patronized the same gay bars in the neighborhood, making it markedly different from most gay enclaves elsewhere in the city. The influx of white gay men in the Fifties and Sixties is often credited with accelerating the gentrification of the Upper West Side.[21]

In a subsequent phase of urban renewal, the rail yards which had formed the Upper West Side's southwest corner were replaced by the Riverside South residential project, which included a southward extension of Riverside Park. The evolution of Riverside South had a 40-year history, often extremely bitter, beginning in 1962 when the New York Central Railroad, in partnership with the Amalgamated Lithographers Union, proposed a mixed-use development with 12,000 apartments, Litho City, to be built on platforms over the tracks. The subsequent bankruptcy of the enlarged, but short-lived Penn Central Railroad brought other proposals and prospective developers. The one generating the most opposition was Donald Trump's "Television City" concept of 1985, which would have included a 152-story office tower and six 75-story residential buildings. In 1991, a coalition of civic organizations proposed a purely residential development of about half that size, and then reached a deal with Trump.[22]

The community's links to the events of September 11, 2001 were evinced in Upper West Side resident and Pulitzer Prize winner David Halberstam's paean to the men of Ladder Co 40/Engine Co 35, just a few blocks from his home, in his book Firehouse.[23]

Today, this area is the site for several long-established charitable institutions; their unbroken parcels of land have provided suitably scaled sites for Columbia University and the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, as well as for some vanished landmarks, such as the Schwab Mansion on Riverside Drive.

The name Bloomingdale is still used in reference to a part of the Upper West Side, essentially the location of old Bloomingdale Village, the area from about 96th Street up to 110th Street and from Riverside Park east to Amsterdam Avenue. The triangular block bound by Broadway, West End Avenue, 106th Street and 107th Street, although generally known as Straus Park (named for Isidor Straus and his wife Ida), was officially designated Bloomingdale Square in 1907. The neighborhood also includes the Bloomingdale School of Music and Bloomingdale neighborhood branch of the New York Public Library. Adjacent to the Bloomingdale neighborhood is a more diverse and less affluent subsection of the Upper West Side called Manhattan Valley, focused on the downslope of Columbus Avenue and Manhattan Avenue from about 96th Street up to 110th Street.

Demographics

[edit]

For census purposes, the New York City government classifies the Upper West Side as part of two neighborhood tabulation areas: Upper West Side (up to 105th Street) and Lincoln Square (down to 58th Street), divided by 74th Street.[24] Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the combined population of the Upper West Side was 193,867, a change of 1,674 (0.9%) from the 192,193 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 1,162.29 acres (470.36 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 166.8 inhabitants per acre (106,800/sq mi; 41,200/km2).[25] The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 69.5% (134,735) White, 7.1% (13,856) African American, 0.1% (194) Native American, 7.6% (14,804) Asian, 0% (48) Pacific Islander, 0.3% (620) from other races, and 2% (3,828) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 13.3% (25,782) of the population.[26]

The racial composition of the Upper West Side changed moderately from 2000 to 2010, with the greatest changes being the increase in the Asian population by 38% (4,100), the decrease in the Black population by 15% (2,435), and the increase in the Hispanic / Latino population by 8% (2,147). The White population remained the majority, experiencing a slight increase of 2% (2,098), while the small population of all other races experienced a negligible increase of 1% (58). Taking into account the two census tabulation areas, the overall decreases in the Black and Hispanic / Latino populations were concentrated in the Upper West Side area, with the Hispanic / Latino population actually increasing by a smaller margin in Lincoln Square. On the other hand, the increases in the White and Asian populations were mostly in Lincoln Center, especially the White population.[27]

The entirety of Community District 7, which comprises the Upper West Side from 59th Street to 110th Street, had 214,744 inhabitants as of NYC Health's 2018 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 84.7 years.[28]: 2, 20 This is higher than the median life expectancy of 81.2 for all New York City neighborhoods.[29]: 53 (PDF p. 84) Most residents are adults: a plurality (34%) are between the ages of 25–44, while 27% are between 45 and 64, and 18% are 65 or older. The ratio of youth and college-aged residents was lower, at 15% and 5% respectively.[28]: 2

As of 2017, the median household income in Community District 7 was $123,894.[30] In 2018, an estimated 9% of Upper West Side residents lived in poverty, compared to 14% in all of Manhattan and 20% in all of New York City. One in twenty residents (5%) were unemployed, compared to 7% in Manhattan and 9% in New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 40% in the Upper West Side, compared to the boroughwide and citywide rates of 45% and 51% respectively. Based on this calculation, as of 2018[update], Community District 7 is not considered to be gentrifying: according to the Community Health Profile, the district was not low-income in 1990.[28]: 7

Political representation

[edit]The Upper West Side is part of Manhattan Community District 7.[1] Politically, the Upper West Side is in New York's 12th congressional district.[31][32] It is in the New York State Senate's 30th and 47th districts,[31][33] the New York State Assembly's 67th, 69th, and 75th districts,[31][34] and the New York City Council's 6th and 7th districts.[31]

Notable structures

[edit]

Organization headquarters

[edit]- American Broadcasting Company – KPF-designed headquarters located at 77 West 66th Street at Columbus Avenue.

- Time Warner – Skidmore, Owings & Merrill-designed headquarters located on Columbus Circle, at the site of the old New York Coliseum.

- Two primary music licensing organizations are located in the neighborhood, ASCAP and BMI.

- Lighthouse Guild – This non-sectarian, non-profit organization serving the visually impaired, blind, and those with multiple disabilities, has its national headquarters on West 64th Street between Amsterdam and West End Avenues.[35]

Cultural institutions

[edit]- American Folk Art Museum

- Eva and Morris Feld Gallery

- American Museum of Natural History

- Hayden Planetarium

- Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation

- Ballet Hispanico Tina Ramirez

- Bach Vespers at Holy Trinity

- Bard Graduate Center Gallery

- Beacon Theatre

- Children's Museum of Manhattan

- Lincoln Center – A total of 12 performing arts companies hosted in a variety of theater and recital spaces

- Metropolitan Opera

- David Geffen Hall (formerly Avery Fisher Hall), home of the New York Philharmonic

- David H. Koch Theater (formerly New York State Theater), home of the New York City Ballet

- Juilliard School of Music

- Jazz at Lincoln Center

- Alice Tully Hall

- Film Society of Lincoln Center

- School of American Ballet

- Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Claire Tow Theater

- Mitzi Newhouse Theater

- Damrosch Park[36]

- New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Bruno Walter Auditorium

- Museum of Biblical Art

- Merkin Concert Hall

- New-York Historical Society

- Nicholas Roerich Museum

- Symphony Space

- Thalia Theater

- El Taller Latinoamericano

Other sites

[edit]

- 27 West 67th Street - Artists' studio cooperative built in 1901, anchor for the West 67th Street Artists' Colony Historic District.

- American Youth Hostel – the transformation of this abandoned Richard Morris Hunt landmark into the flagship of Hostelling International USA was propelled forward by the federal Community Development Block Grant funded, Manhattan Valley Neighborhood Strategy Area designation.[37]

- Apple Bank Building – formerly Central Savings Bank, a Florentine palazzo at Broadway and 73rd, with a Roman banking hall, one of New York's classic interior spaces, York & Sawyer, architects, ironwork by Samuel Yellin, 1928. The upper floors have been converted to luxury condominium apartments.

- Claremont Riding Academy – In 2007, after 115 years of use, the last public stables in Manhattan, this National Register building on 89th Street, just east of Amsterdam, closed its doors for good.[38][39] The subsequent interior gutting for conversion to residential use has halted.

- Columbus Circle – Traffic circle at the intersection of Broadway, Central Park West and Eighth Avenue, and Central Park South. Its centerpiece is a statue of the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus erected in 1906. Two other similarly financed monuments on Broadway include those to Italian writer Dante Aligheri in Dante Park between 63rd and 64th Streets at Columbus Avenue (which now heralds Lincoln Center); and to Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi which anchors Verdi Square, girded by 72nd and 73rd Streets at Amsterdam Avenue. The square, which actually was a triangle, was expanded to allow for a new subway head house and a plaza which became the setting for summer concerts. The aforementioned Apple Bank is across from the statue, and the Ansonia Hotel lies diagonally across the northwest intersection.

- The Dakota is a co-op apartment building on 72nd Street and Central Park West, which is New York City's oldest surviving luxury apartment building.[40] The musician John Lennon was murdered there in 1980.[41]

- Strawberry Fields is a landscaped section of Central Park opposite the Dakota. It is dedicated to the memory of John Lennon, with an inlaid mosaic of "Imagine", surrounded by benches where people gather to remember Lennon.[42]

- The former East River Savings Bank at Amsterdam Avenue and 96th Street (Walker & Gillette, 1927) is a classical temple now housing a drugstore, locally termed "The Aspirineum" and "The First National Bank of CVS"[43]

- Firemen's Memorial – this 1913 monument on Riverside Drive at 100th Street has been the scene of somber gatherings and spontaneous gestures, such as a display of flowers and children's teddy bears on 9/11. The Piccirilli Brothers' female model for this work, Audrey Munson, sat for the nearby Straus Memorial and for their Maine Monument, as well.[44]

- Grant's Tomb – in Morningside Heights

- Joan of Arc Monument – a monument to the 15th-century French heroine bestrides a horse on a crest of Riverside Drive at 93rd Street.[45]

- Soldiers' & Sailors' Monument – this Civil War memorial dominating Riverside Drive at 89th Street, is the setting for annual Memorial Day commemorations.[46]

- Isidor and Ida Straus Memorial – honors Isidor Straus, co-owner of Macy's, and his wife, who lived in a mansion on West End Avenue and 105th Street, and died on the RMS Titanic, in triangular Straus Park at Broadway, West End Avenue and West 106th Street. The model for the sculpture[46] was also the muse for the Maine Monument,[47] 57 blocks south on Broadway, at the Columbus Circle entrance to Central Park.

Residences

[edit]

The apartment buildings along Central Park West, facing the park, are some of the city's most opulent. The Dakota at 72nd Street has been home to numerous celebrities including John Lennon, Leonard Bernstein, and Lauren Bacall.[48] Other buildings on CPW include four twin-towered structures: the Century and Majestic by Irwin Chanin, the Orwell House by the firm of Mulliken and Moeller, and the San Remo and El Dorado by Emery Roth.[49] Roth also designed the Beresford, the Alden, and the Ardsley on Central Park West.[50] His first major commission, the Belle Époque-style Belleclaire Hotel, is on Broadway,[51] while the moderne-style Normandy stands on Riverside at 86th Street.[52] Along Broadway are several large apartment houses, including the Belnord (1908), the Apthorp (1908), the Ansonia (1902),[53] the Dorilton (1902),[54] and the Manhasset.[55] All are individually designated New York City landmarks.

The serpentine Riverside Drive also has many pre-war houses and larger buildings, while West End Avenue is lined with pre-war Beaux-Arts apartment buildings and townhouses dating from the late-19th and early 20th centuries. Columbus Avenue north of 87th Street was the spine for major post-World War II urban renewal. Broadway is lined with such architecturally notable apartment buildings as The Ansonia, The Apthorp, The Belnord, the Astor Court Building, and The Cornwall, which features an Art Nouveau cornice.[56][57] Newly constructed 15 Central Park West and 535 West End Avenue are among some of the prestigious residential addresses in Manhattan.

Restaurants and gourmet groceries

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

Both Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue from 67th Street up to 110th Street are lined with restaurants and bars, as is Columbus Avenue to a slightly lesser extent. The following lists a few prominent ones:

- Barney Greengrass, specializing in fish at Amsterdam Avenue and 86th Street; featured in the 2011 film Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close. It marked its centenary in June 2008.[58]

- Citarella Gourmet Market (flagship store), specializing in seafood, meats and gourmet packaged foods located at 75th Street[59]

- The Howard Chandler Christie murals of Café des Artistes, a now-closed French restaurant on West 67th Street off Central Park West, are being incorporated into a new restaurant on the site.

- Cafe Lalo, dessert and coffee venue at 83rd Street and Amsterdam Avenue, opened in 1988 and featured in the 1998 movie You've Got Mail.[60]

- Community Food and Juice, an eco-conscious restaurant at 2893 Broadway between 112th and 113th Streets.[61]

- A branch of Gray's Papaya, which specializes in hot dogs, is located at Broadway and 72nd Street.

- The original Zabar's is a specialty food and housewares store at Broadway and 80th Street.

- Levana's, a kosher, fine dining restaurant was part of the neighborhood for three decades, but closed in the 2000s.[62]

- Tom's Restaurant located on the ground floor of the Columbia University's Armstrong Hall at 2880 Broadway on the northeast corner of 112nd Street, was used as the outside location for the fictional Monk's Cafe in the NBC show Seinfeld.[63]

Police and crime

[edit]The Upper West Side is patrolled by two precincts of the NYPD.[64] The 20th Precinct is located at 120 West 82nd Street and serves the part of the neighborhood south of 86th Street,[65] while the 24th Precinct is located at 151 West 100th Street and serves the part of the neighborhood north of 86th Street.[66]

The 20th Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 95.5% between 1990 and 2022. The precinct reported 0 murders, 14 rapes, 116 robberies, 102 felony assaults, 136 burglaries, 877 grand larcenies, and 75 grand larcenies auto in 2022.[67] Of the five major violent felonies (murder, rape, felony assault, robbery, and burglary), the 20th Precinct had a rate of 250 crimes per 100,000 residents in 2019, compared to the boroughwide average of 632 crimes per 100,000 and the citywide average of 572 crimes per 100,000.[68][69][70]

The 24th Precinct also has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 94.1% between 1990 and 2022. The precinct reported 1 murder, 9 rapes, 150 robberies, 188 felony assaults, 180 burglaries, 526 grand larcenies, and 89 grand larcenies auto in 2022.[71] Of the five major violent felonies (murder, rape, felony assault, robbery, and burglary), the 24th Precinct had a rate of 414 crimes per 100,000 residents in 2019, compared to the boroughwide average of 632 crimes per 100,000 and the citywide average of 572 crimes per 100,000.[68][69][70]

As of 2018[update], Manhattan Community District 7 has a non-fatal assault hospitalization rate of 25 per 100,000 people, compared to the boroughwide rate of 49 per 100,000 and the citywide rate of 59 per 100,000. Its incarceration rate is 211 per 100,000 people, compared to the boroughwide rate of 407 per 100,000 and the citywide rate of 425 per 100,000.[28]: 8

In 2019, the highest concentration of felony assaults and robberies in the Upper West Side was on Columbus Avenue between 100th Street and 104th Street (going through the Frederick Douglass Houses), where there were 24 felony assaults and 15 robberies. The area around the intersection of 72nd Street and Broadway also had 14 robberies in 2019.[68]

Fire safety

[edit]The Upper West Side is served by multiple New York City Fire Department (FDNY) fire stations:[72]

- Engine Company 40/Ladder Company 35 – 131 Amsterdam Avenue[73]

- Ladder Company 25/Division 3/Collapse Rescue 1 – 205 West 77th Street[74]

- Engine Company 74 – 120 West 83rd Street[75]

- Engine Company 76/Ladder Company 22/Battalion 11 – 145 West 100th Street[76]

Health

[edit]As of 2018[update], preterm births and births to teenage mothers in the Upper West Side are lower than the city average. In the Upper West Side, there were 78 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 87 per 1,000 citywide), and 7.1 births to teenage mothers per 1,000 live births (compared to 19.3 per 1,000 citywide).[28]: 11 The Upper West Side has a low population of residents who are uninsured. In 2018, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 5%, less than the citywide rate of 12%, though this was based on a small sample size.[28]: 14

The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in the Upper West Side is 0.0083 milligrams per cubic metre (8.3×10−9 oz/cu ft), more than the city average.[28]: 9 Ten percent of Upper West Side residents are smokers, which is less than the city average of 14% of residents being smokers.[28]: 13 In the Upper West Side, 10% of residents are obese, 5% are diabetic, and 21% have high blood pressure—compared to the citywide averages of 24%, 11%, and 28% respectively.[28]: 16 In addition, 10% of children are obese, compared to the citywide average of 20%.[28]: 12

Ninety-two percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, which is higher than the city's average of 87%. In 2018, 93% of residents described their health as "good", "very good", or "excellent", the highest rate in the city and more than the city's average of 78%.[28]: 13 For every supermarket in the Upper West Side, there are 3 bodegas.[28]: 10

Mount Sinai Urgent Care Upper West Side is located in the Upper West Side.[77][78]

Post offices and ZIP Codes

[edit]Upper West Side is located in three primary ZIP Codes. From south to north, they are 10023 south of 76th Street, 10024 between 76th and 91st Streets, and 10025 north of 91st Street. In addition, Riverside South is part of 10069.[79] The United States Postal Service operates five post offices in the Upper West Side:

- Ansonia Station – 178 Columbus Avenue[80]

- Cathedral Station – 215 West 104th Street[81]

- Columbus Circle Station – 27 West 60th Street[82]

- Park West Station – 700 Columbus Avenue[83]

- Planetarium Station – 127 West 83rd Street[84]

Education

[edit]

The Upper West Side generally has a higher rate of college-educated residents than the rest of the city as of 2018[update]. A majority of residents age 25 and older (78%) have a college education or higher, while 6% have less than a high school education and 16% are high school graduates or have some college education. By contrast, 64% of Manhattan residents and 43% of city residents have a college education or higher.[28]: 6 The percentage of the Upper West Side students excelling in math rose from 35% in 2000 to 66% in 2011, and reading achievement increased from 43% to 56% during the same time period.[85]

The Upper West Side's rate of elementary school student absenteeism is lower than the rest of New York City. In the Upper West Side, 14% of elementary school students missed twenty or more days per school year, less than the citywide average of 20%.[29]: 24 (PDF p. 55) [28]: 6 Additionally, 83% of high school students in the Upper West Side graduate on time, more than the citywide average of 75%.[28]: 6

Schools

[edit]Public

[edit]The New York City Department of Education operates the following public elementary schools in the Upper West Side:[86]

- PS 9 Sarah Anderson (grades PK-5)[87]

- PS 75 Emily Dickinson (grades K-5)[88]

- PS 84 Lilian Weber (grades PK-5)[89]

- PS 87 William Sherman (grades PK-5)[90]

- PS 145 The Bloomingdale School (grades PK-5)[91]

- PS 163 Alfred E Smith (grades PK-5)[92]

- PS 165 Robert E Simon (grades PK-8)[93]

- PS 166 The Richard Rogers School of the Arts and Technology (grades K-5)[94]

- PS 191 The Riverside School for Makers and Artists (grades PK-8)[95]

- PS 199 Jessie Isador Straus (grades K-5)[96]

- PS 212 Midtown West (grades PK-5)[97]

- PS 333 Manhattan School For Children (grades K-8)[98]

- PS 452 (grades PK-5)[99]

- PS 811 Mickey Mantle School (grades PK-9)[100]

- Special Music School (grades K-12)[101]

- The Anderson School (grades K-8)[102]

The following public middle schools serves grades 6-8 unless otherwise indicated:[86]

The following public high schools serve grades 9-12 unless otherwise indicated:[86]

- Edward A. Reynolds West Side High School[112]

- Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School – a specialized high school[113]

- Martin Luther King Jr. Educational Campus

- Louis D. Brandeis High School Campus

- Frank McCourt High School[119]

- Innovation Diploma Plus (grades 10–12)[120]

- The Global Learning Collaborative[121]

- Urban Assembly School for Green Careers[122]

Charter and private

[edit]The following charter and private schools are located in the Upper West Side:[86]

- Abraham Joshua Heschel School

- Lower and Middle Schools – West End Avenue at West 61st Street

- High School – West End Avenue at West 60th Street

- Alexander Robertson School – West 95th Street off Central Park West

- Ascension School – (Pre-K3 through 8), 220 West 108th Street (between Broadway and Amsterdam)

- Bank Street School for Children

- Beit Rabban Day School – an innovative, non-denominational day school combining intellectual rigor, serious Jewish learning, and a progressive educational approach

- Bloomingdale School of Music

- Calhoun School

- Main Building – 433 West End Avenue at 81st Street.

- Robert L. Beir Lower School – 160 West 74th Street, between Amsterdam & Columbus avenues.

- The Center School [This is not a charter or private school. See MS 243 Center School above.]– 84th street, between Columbus & Amsterdam Avenues

- The Collegiate School – Central Park West and 63rd Street

- Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School

- Columbus Academy

- Dwight School

- Ethical Culture Fieldston School

- La Salle Academy

- Lucy Moses School

- The Mandell School

- Manhattan Day School

- Rodeph Sholom School

- School of the Blessed Sacrament – 140 West 70th Street

- Solomon Schechter School of Manhattan (2–8 West 89th)

- St. Agnes Boys High School

- The Studio School

- Success Academy Upper West

- Trevor Day School (Lower)

- Trinity School

- Twin Parks Montessori Schools

- Central Park Montessori – 1 West 91st Street

- Park West Montessori – 435 Central Park West

- Riverside Montessori – 202 Riverside Drive

- Yeshiva Ketana of Manhattan occupies Herts & Tallent's 1903 Beaux Arts Rice Mansion at 346 West 89th Street and Riverside Drive.

- York Preparatory School – 40 W 68th St

Higher education

[edit]- The Richard Gilder Graduate School at American Museum of Natural History – Central Park West & West 79th Street

- The American Musical and Dramatic Academy – 211 W 61st Street, between Amsterdam & West End Avenues.

- Columbia University – in Morningside Heights

- Bank Street College of Education and School for Children – in Morningside Heights

- Bard Graduate Center at 86th and Columbus.

- Barnard College – one of the Seven Sisters in Morningside Heights

- Fordham University Lincoln Center campus – Schools of Law, Business, Social Service and Education

- Jewish Theological Seminary of America – in Morningside Heights

- The Juilliard School

- Lander College for Women, a division of Touro College, West 60th Street between Amsterdam and West End Avenues.

- New York Institute of Technology – in the Columbus Circle proximity

- New York Theological Seminary – in Morningside Heights

- William E. Macaulay Honors College – this collaborative endeavor of CUNY's senior colleges occupies the 92nd St Y's former Makor/Steinhardt Building on West 67th Street, east of Columbus Avenue, the latter having relocated to Tribeca.

- Manhattan School of Music – in Morningside Heights

- Mannes College The New School for Music, a division of The New School, on 85th Street between Amsterdam and Columbus

- Teachers College of Columbia University, in Morningside Heights

- Union Theological Seminary – in Morningside Heights

Libraries

[edit]

The New York Public Library (NYPL) operates four branches in the Upper West Side, of which three are circulating branches and one is a reference branch.

- The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (LPA) is a reference branch located at 40 Lincoln Center Plaza. It houses one of the world's largest collections of materials relating to the performing arts. The LPA also contains a circulating collection.[123]

- The Bloomingdale branch is a circulating branch located at 127 East 58th Street. It was founded in 1897 as a New York Free Circulating Library branch and became an NYPL branch in 1901. The Bloomingdale branch moved to its current two-story location in 1961.[124]

- The Riverside branch is a circulating branch located at 127 Amsterdam Avenue (at West 65th St). It was founded in 1897 as a New York Free Circulating Library branch and became an NYPL branch in 1901. The Riverside branch was housed in a Carnegie library building at 190 Amsterdam Avenue from 1904 until 1969, when the structure was replaced. In 1992, it moved to its current two-story space near Lincoln Center.[125]

- The St Agnes branch is a circulating branch located at 444 Amsterdam Avenue (near West 81st St). It was founded in 1893 as the St. Agnes Chapel's parish library and became an NYPL branch in 1901. The current Carnegie library building opened in 1906.[126]

Houses of worship

[edit]

- Fourth Universalist Society in the City of New York – known as the "Cathedral of Universalism". Founded in 1838, it is a member of the Unitarian Universalist Association and is located at 76th Street and Central Park West. The current building was designed by William Appleton Potter in 1898 and features stained glass by Clayton and Bell of London, an altar by Louis Tiffany and a relief sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Notable parishioners include P.T. Barnum, Horace Greeley, and Louise Carnegie, who donated the church's organ.

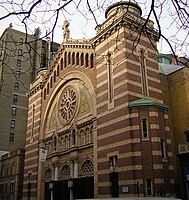

- The Church of St. Paul the Apostle – Late Gothic Revival-Style Building at the corner of West 60th Street and Columbus Avenue that is the mother church of the Paulist Fathers.[127] The sanctuary houses a large organ of 4,965 pipes, built by M. P. Moller in 1965.[128]

- Cathedral of Saint John the Divine – in Morningside Heights, set to be the largest Gothic cathedral in the world if completed. Suffered significant fire damage to the South transept in December 2001. The church was originally to follow a Byzantine-Romanesque design, but the builders switched to a Gothic design along the way. The church plans to replace the great dome with a massive Gothic tower, but this major construction project is likely to take decades.

- Redeemer Presbyterian Church – The West Side congregation of Redeemer Presbyterian Church, at 150 West 83rd St., between Amsterdam and Columbus[129]

- First Baptist Church in the City of New York 79th Street at Broadway

- West-Park Presbyterian Church, designed by Leopold Eidlitz

- Christ and Saint Stephen's Church (Episcopal). Built 1880.

- The Church of St. Gregory the Great – Roman Catholic parish and school on West 90th Street between Amsterdam and Columbus avenues. During the Vietnam War, it was the sanctuary for celebrated fugitive priest Philip Berrigan, who with his fellow priest brother Daniel was then one of the FBI's "10 Most Wanted".[130] More recently, Irish author Colm Tóibín wrote of the church's choir.[131]

- United Methodist Church of St. Paul & St. Andrew – West End Avenue and 86th Street. Center of strong community outreach programs to the disaffected.

- The Jewish Center, located on West 86th Street between Columbus and Amsterdam avenues.

- Ansche Chesed

- B'nai Jeshurun – In 1825, Ashkenazi members left the city's first Jewish house of worship, the Sephardic Congregation Shearith Israel, beginning a trek up Manhattan that would land them on West 88th Street between West End Avenue and Broadway. The 1919 building designed by Broadway theater architect Henry B. Herts with fellow congregant Walter S. Schneider, became a must see for boards of other synagogues then seeking to build new homes. A spiritual and demographic renaissance began in 1985, with the arrival of Rabbi Marshall Meyer.

- Congregation Habonim – founded by refugees on the first anniversary of the Kristallnacht, this congregation occupies a classic post-World War II suburban style synagogue at 44 West 66th Street just off of Central Park West.

- Congregation Shaare Zedek (New York City) West 93rd Street, between Broadway and Amsterdam.

- Congregation Shearith Israel – oldest Jewish congregation in what is now the United States was launched in 1655. Its landmark, 1897 building on Central Park West at West 70th Street was designed by Arnold Brunner and Thomas Tryon and incorporated elements of its first New Amsterdam sanctuary in its small chapel.

- Congregation Rodeph Sholom 83rd Street/Central Park.

- Holy Name of Jesus R.C. Church – 207 West 96th Street, NW corner of Amsterdam. Built 1892–1900; restored 1998–2000.

- Congregation Ohab Zedek

- Kehilat Orach Eliezer

- Kol Zimrah

- Manhattan New York Temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 65th Street and Columbus/Broadway, across the street from Lincoln Center.

- National Council of Churches – prime ecumenical tenant of the Interchurch Center, 120th St. and Riverside Drive.

- Riverside Church – in Morningside Heights

- Rutgers Presbyterian Church – "More Light" Presbyterian Congregation just off Verdi Square and 72nd Subway Station on 236 W. 73rd Street

- St. Michael's Traditional Anglican and emerging church/Seeker worship services at Amsterdam Ave and W 99th Street

- St. Ignatius of Antioch Episcopal Church – Excellent example of Anglican "high church" architecture at 87th Street and West End Avenue

- Society for Ethical Culture, also a classical music venue

- Society for the Advancement of Judaism

- Stephen Wise Free Synagogue

-

Roman Catholic Church of the Holy Trinity 213 West 82nd Street

-

St. Volodymyr Ukrainian Orthodox Church, formerly home to Temple Shaarey Tefila, 180 West 82d Street

-

Young Israel of the Upper West Side

-

Cong Ohav Sholom

Transportation

[edit]Two New York City Subway corridors serve the Upper West Side. The IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line (1, 2, and 3 trains) runs below Broadway, and the IND Eighth Avenue Line (A, B, C, and D trains) runs below Central Park West.[132]

There are five bus routes – M5, M7, M10, M11, M104 buses – that go up and down the Upper West Side, and the M57 goes up West End Avenue for 15 blocks in the neighborhood. Additionally, crosstown routes include the M66, M72, M79 SBS, M86 SBS, M96 and M106. The north–south M20 terminates at Lincoln Center.[133]

In popular culture

[edit]The Upper West Side has been a setting for many films and television shows.

Films

[edit]In alphabetical order:

- American Psycho (2000) Christian Bale's character (Patrick Bateman) lives at 55 West 81st Street, named as the American Gardens Building.

- The Apartment (1960)

- Black and White (1999), has scenes of Central Park and Columbia University

- Black Swan (2010) The main character, Nina, played by Natalie Portman, states that she lives on Manhattan's upper west side.

- Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006) Early on in his trip to America, Borat is seen in Columbus Circle in front of the Trump International Hotel and Tower

- Death Wish (1974), where the main character, Paul Kersey, played by Charles Bronson, lives in between Riverside Drive and West End Avenue

- Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995), includes a scene set outside the subway station at 72nd Street and Broadway, featuring a public phone that was in fact only a prop.

- Elf (2003), includes a scene when Buddy's brother leaves school (York Prep) at 40 West 68th Street.

- Enchanted (2007), Robert & Morgan live in a building on the corner of Riverside Drive and 116th Street, Robert's office is in the Time Warner Center on Columbus Circle.

- Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011) The Schell family lives at The Gramont, 215 West 98th Street.

- Eyes Wide Shut (1999) The characters played by Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman live in an apartment on Central Park West.

- Fools Rush In (1997) Several scenes, including the 72nd St. & Broadway Subway station and CPW

- Fatal Attraction (1987) In the film, Michael Douglas' character lives in a building on 100th and West End Avenue

- Ghostbusters (1984) At the opening the title characters shown being ousted professors on the Columbia University campus, and Sigourney Weaver's character lives in 55 Central Park West, at 66th St.

- The Goodbye Girl (1977) Filmed at 170 West 78th Street off Amsterdam Avenue. Starring Richard Dreyfuss and Marsha Mason

- Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) Hannah's parents' apartment is shown on Riverside and 86th Street, and near the end of the film Woody Allen's character is seen walking along Broadway between 92nd and 93rd Streets and then entering the Metro Theatre at Broadway between 99th and 100th Streets.

- Heartburn (1986), finds Meryl Streep's character taking refuge in her father's spacious apartment at the Apthorp on 79th Street and Broadway after her marriage fails; author Nora Ephron, on whose novel the film was based, was an Apthorp resident at the time.

- Home Alone 2: Lost in New York (1992), takes place in Central Park, and in a townhouse on 95th St. as well as other locations throughout New York.

- Hitch (2005), starts with Will Smith's character Hitch, exiting 865 West End Avenue, 102nd Street, apartment building.

- The House on 92nd Street (1945), though set on the Upper East Side at 92nd/Madison, the film is based on the true story of Nazi spies operating out of an Upper West Side boarding house on 90th Street between Amsterdam/Columbus.

- Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), the main character would sometimes sleep on the couch of his friends, the Gorfeins, who live in an apartment on the Upper West Side.

- Keeping the Faith (2000), various church and synagogue locations

- Kissing Jessica Stein (2002)

- A Late Quartet (2012), Time Warner Center at Columbus Circle and Central Park

- Little Manhattan (2005) – includes scenes from the American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West, Broadway at 72nd Street, and Septuagesimo Uno – the city's smallest public park, located on W. 71st Street between Amsterdam and West End Avenues.

- I Am Legend (2007) – featuring Will Smith, the now demolished Red Cross building on 66th and Amsterdam was used for many indoor "zombie" scenes.

- Margaret (2011) – featuring Matt Damon, in the opening scene 17-year-old Manhattan student Lisa Cohen, shopping on the Upper West Side, interacts with bus driver Gerald Maretti as she runs alongside his moving bus.

- Men in Black II (2002) – featuring Tommy Lee Jones and Will Smith, outside in front of Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History.

- The Mirror Has Two Faces (1996) – The romantic comedy by Barbra Streisand was set in an apartment at 505 West End Avenue.

- Music and Lyrics (2007) – featuring Hugh Grant and Drew Barrymore. The area around 72nd Street which forms the backdrop for Grant's apartment. The restaurant scene was shot at La Fenice at 69th and Broadway.

- New York Minute (2004) – features Ashley Olsen's character making a speech at Columbia.

- Night at the Museum (2006) – is set in the Museum of Natural History and areas adjoining it.

- The Odd Couple (1968) The apartment owned by Oscar Madison, played by Walter Matthau, was at 131 Riverside Drive; the rooftop used was at 190 Riverside.

- Panic Room (2002) – takes place on West 94th Street.

- The Panic in Needle Park (1971) and the 1966 novel by James Mills) – set in Sherman Square, at Broadway and 70th Street.

- The Pawnbroker (1964) – One of the final scenes is at Geraldine Fitzgerald's character's apartment in Lincoln Towers.

- Prime (2005) – Uma Thurman gets her nails done at Pinky's on 89th Street.

- Premium Rush (2012) – Wilee is seen evading police near the American Museum of Natural History

- Romancing the Stone (1984) – Kathleen Turner's character lives on West End Avenue.

- Rosemary's Baby (1968) – The Dakota is shown

- Seize the Day (1986) – like the Saul Bellow novel from which it is adapted, is set in an old residential hotel on Broadway in the West 70s; exterior location filming was done there.

- Single White Female (1992) – The Ansonia is shown

- Spider-Man (2002) – Low Library and College Walk of Columbia University

- Spider-Man 2 (2004) – Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History

- Starting Out in the Evening (2007) and the 1998 novel by Brian Morton

- Take the Money and Run (1969) – Virgil and Louise are seen at the fountain in Lincoln Center

- Three Men and a Baby (1987) – Tom Selleck's character is Peter Mitchell whose apartment is at The Prasada, 50 Central Park West

- Up the Sandbox (1972) – In the Columbia University area and in Riverside Park

- Vanilla Sky (2001) – car accident at center of film happens in Riverside Park, near 96th Street

- Wall Street (1987) – In one of the final scenes, after being punched in Central Park by Michael Douglas for being unloyal, Charlie Sheen walks into the Tavern on the Green where he provides evidence implicating Douglas in federal security fraud. Bud Fox Charlie Sheen's initial small apartment is described as being on the Upper West Side.

- Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010) – Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas) rents a penthouse in a building located in the Upper West Side next to Fordham University with a penthouse facing downtown. In one of the scenes, Jake Moore (Shia LaBeouf) visits him at this penthouse.

- The Warriors (1979) – The Warriors emerge from the 72nd street subway station (Baseball Furie's Turf) and run to Riverside Park, where they easily defeat The Baseball Furies. The meeting at the beginning of the film is also conducted in Riverside Park, though it is mislabeled as Van Cortlandt Park.

- West Side Story (1961) – takes place in tenements where Lincoln Center is today, around 66th Street

- You've Got Mail (1998) – Meg Ryan and Tom Hanks's characters live on the Upper West Side, and various locations were used in the film

Television

[edit]In alphabetical order:

- Central Park West - Mid 1990s prime time soap opera about a glossy magazine, its owners and employees.

- Foley Square – Margaret Colin's character Alex Harrigan and Michael Lembeck's character Peter Newman live in an apartment building on the Upper West Side.

- Gossip Girl – The Empire Hotel is Chuck Bass's hotel and is located at 64th Street and Broadway, just north of Columbus Circle.

- The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - It is mentioned in season 1, episode 1 (and other episodes), that Mrs. Maisel lives in Upper West Side.

- The Night Of – It is mentioned in season 1, episode 1, that the murder which is the primary focus of the storyline occurred at a residence on the Upper West Side.

- The Odd Couple – In one episode (season 4, episode 6), Oscar and Felix give the address of their apartment as West 74th Street and Central Park West (series star Tony Randall actually did live at The San Remo on CPW between West 74th and 75th Streets), although in another episode, the guys' address is given as 1095 Park Avenue, all the way across Manhattan on the Upper East Side. The original Neil Simon stage play from which the subsequent film and various TV adaptions were derived was set on Riverside Drive in the West 80s.

- Only Murders in the Building – The show is set in the Belnord where Steve Martin, Martin Short and Selena Gomez' characters are investigating a murder in said building, "The Arconia".

- Ryan's Hope – The series' principal family, the Ryans, lived and owned a bar on the Upper West Side.

- Seinfeld – Jerry Seinfeld as the character in the series lived at 129 West 81st Street, though the establishing exterior shots were of a building in Los Angeles; the series used authentic exteriors from locations such as Tom's Restaurant and H&H Bagels. (Jerry Seinfeld himself is an owner of an apartment in The Beresford at 81st Street and Central Park West.)

- Sesame Street - The inspiration for the show's location.

- Sex and the City – The series used many locations, including Gray's Papaya, Zabar's, and Charlotte's (275 CPW) and Miranda's (250 W. 85th) apartments.

- Will & Grace – Will lives in 155 Riverside Drive, Apartment 9C. Jack lives in 155 Riverside Drive, Apartment 9A.

Music

[edit]In alphabetical order:

- The Beastie Boys played their first gig in a loft at 100th and Broadway, and recorded some tracks for the EP Polywog Stew there in 1981.[134][135]

- "Classical Rap" – This parody by Peter Schickele, on his album P. D. Q. Bach: Oedipus Tex & Other Choral Calamities, describes the travails of living on the Upper West Side, as a Yuppie chants hip-hop lyrics to a classical instrumental background.

- "Lazy Sunday" – A parody rap on the late-night sketch comedy show Saturday Night Live (December 2005), performed by Andy Samberg and Chris Parnell about their day going to see The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and getting cupcakes. The song's lyrics mention that they see the film at a theater on 68th Street and Broadway. While there is indeed an AMC movie theater on that corner, the video shows them at a ticket booth for an entirely different theater (on 84th and Broadway).

- Lynn Oliver had his recording studio sandwiched next to the New Yorker Bookshop and Benny's on 89th Street and Broadway. Sonny Rollins, Chet Baker, and Stan Getz, among others, could be seen ducking into his alley-like studio to practice and hangout. Oliver's credits are found on a few classic cuts from the '60s.

- "Tom's Diner" – A song by Suzanne Vega focusing on a woman on a rainy morning at Tom's Restaurant at 112th and Broadway.[136]

Books

[edit]- The Tale of the Allergist's Wife, 1999 play by Charles Busch[137]

- When You Reach Me, 2009 novel by Rebecca Stead set in the Upper West Side of the author's childhood.[138]

- Rosemary's Baby by Ira Levin[139]

- The Panic in Needle Park by James Mills[140]

- The Princess of 72nd Street, a 1979 novel by Elaine Kraf (the protagonist identifies herself as the titular princess of 72nd street on the Upper West Side)[141]

- The Ruined House by Reuven (Ruby) Namdar.

- Seize the Day by Saul Bellow[142]

- Starting Out in the Evening by Brian Morton[143]

- Gangsterland: A Tour Through the Dark Heart of Jazz-Age New York City by David Pietrusza

- The Bonfire of the Vanities by Tom Wolfe

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "NYC Planning | Community Profiles". communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov. New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ "Upper West Side neighborhood in New York". Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055366.

- ^ "Upper West Side" Archived November 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, nymag.com. Accessed May 10, 2009. "Boundaries: Extends north from Columbus Circle at 59th Street up to 110th Street, and is bordered by Central Park West and Riverside Park."

- ^ Eric W. Sanderson, Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City, 2009, map "Habitat Suitability for People" p. 111.

- ^ Sanderson 2009, map "Native American Fires" p. 127.

- ^ A colonial brick house with a hipped roof, above a lawn neatly enclosed by a white picket fence sloping down to the Bloomingdale Road appears in a daguerreotype of c. 1848 that was sold at Sotheby's New York, 30 March 2009 Archived May 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ O'Brien, Jessica Lynn. "Unearthing Bloemendaal". Cooperator. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ West 105th Street Historic District Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, nyc.gov.

- ^ "Harsenville District". Rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Dolkart, Andrew S. (1998). Morningside Heights: A History of its Architecture and Development. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-231-07850-4. OCLC 37843816.

- ^ "Bloomingdale Insane Asylum – WikiCU, the Columbia University wiki encyclopedia". Wikicu.com. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ Caro, Robert (1974). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-48076-3. OCLC 834874.

- ^ "NYC Parks Press Release". Nycgovparks.org. November 13, 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ "Gay Midnight Crowd Rides First Trains in New Subway". The New York Times. September 10, 1932. p. 1.

- ^ "www.nycsubway.org: The 9th Avenue Elevated-Polo Grounds Shuttle". Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ Waxman, Sarah. "The History of the Upper West Side" Archived March 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, NY.com. Accessed July 7, 2007. "Home to such venerable New York landmarks as Lincoln Center, Columbia University, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, the Dakota Apartments, and Zabar's food emporium, the Upper West Side stretches from 59th Street to 125th Street, including Morningside Heights. It is bounded by Central Park on the east and the Hudson River on the west."

- ^ "About Lincoln Center" Archived May 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, City Realty.

- ^ "The Jewish West Side of New York City, 1920-1970". ProQuest.

- ^ Bleyer, Jennifer (August 9, 2008). "Marriage on Their Minds". The New York Times. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- ^ "Travel > Walking Tour of the Upper West Side". The New York Times. October 29, 2002. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ Kruse, Michael (June 29, 2018). "The Lost City of Trump". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ "Halberstam's Heroes" Archived August 7, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Firehouse review by John Homans, New York, (undated)

- ^ New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived November 29, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- ^ Table PL-P5 NTA: Total Population and Persons Per Acre - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- ^ Table PL-P3A NTA: Total Population by Mutually Exclusive Race and Hispanic Origin - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, March 29, 2011. Accessed June 14, 2016.

- ^ "Race / Ethnic Change by Neighborhood" (Excel file). Center for Urban Research, The Graduate Center, CUNY. May 23, 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Upper West Side (Including Lincoln Square, Manhattan Valley and Upper West Side)" (PDF). nyc.gov. NYC Health. 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "2016-2018 Community Health Assessment and Community Health Improvement Plan: Take Care New York 2020" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ "NYC-Manhattan Community District 7--Upper West Side & West Side PUMA, NY". Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Current NYC District Maps | NYC Board of Elections". vote.nyc. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ "NYS Congressional Districts". data.gis.ny.gov. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ "NYS Senate Districts". data.gis.ny.gov. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ "NYS Assembly Districts". data.gis.ny.gov. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ "Lighthouse Guild · 250 W 64th St, New York, NY 10023".

- ^ "Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Inc". www.lincolncenter.org. Archived from the original on November 20, 2007.

- ^ Richard D. Lyons (March 27, 1988). "West Side Landmark to Become a Hostel". The New York Times. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ "Potomac Horse Center – Claremont Riding Academy". Potomachorse.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny (May 26, 2007). "The Last of the Last: 3 Horses in a Stable of Empty Stalls". The New York Times.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (September 9, 1984). "Architecture Will Mainly Be Seen in Museums". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ Ledbetter, Les (December 9, 1980). "John Lennon of Beatles Is Killed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ "Strawberry Fields in Central Park : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. December 8, 1980. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ^ East River Savings Bank Archived October 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, neighborhoodpreservationcenter.org.

- ^ "Riverside Park Monuments – Firemen's Memorial : NYC Parks". Nycgovparks.org. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ "Riverside Park Fund: Joan of Arc Monument". www.riversideparkfund.org. Archived from the original on January 25, 2008.

- ^ a b "New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs". dmna.ny.gov. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ "Central Park Conservancy: Maine Monument". www.centralparknyc.org. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009.

- ^ Carroll, June (March 6, 1967). "One of New York's oldest status symbols". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 12. ProQuest 510962323.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (December 19, 1999). "Streetscapes/The San Remo; 400-Foot-High Twin Towers of Central Park West". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ Alpern, Andrew. Apartments for the Affluent: a Historical Survey of Buildings in New York. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975.

- ^ Holusha, John (June 29, 2003). "Commercial Property/Upper West Side; Flamboyant Landmark Hotel, Restored for Tourists". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ Postal, Matthew A.; Dolkart, Andrew; New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (2009). Guide to New York City Landmarks. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1. OCLC 226308081.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (August 9, 1987). "Streetscapes: the 81st Street Theater; The Curtain Falls, but Preservation Is in the Wings". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Apartment Houses of New York". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 85, no. 2193. March 26, 1910. pp. 644–645 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Manhasset Apartments, 2801–2815 Broadway, 301 West 108th Street and 300 West 109th Street, Landmarks Preservation Commission, May 1996

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. "The Cornwall" Archived February 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine City Review

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot (2000). AIA Guide to New York City (Fourth ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 351. ISBN 0-8129-3107-6.

- ^ Albrecht, Leslie. "Barney Greengrass Stars in Tom Hanks Movie Shoot". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ "Shopping Aisle: The Upper West Side is Still a Manhattan Foodie's Mecca". Observer. December 2, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ Munoz, Cassandra (October 18, 2013). "Film Locations: You've Got Mail on the Upper West Side". Untapped Cities. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ Moskin, Julia (January 30, 2008). "Dining Briefs; Community Food and Juice". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ Brawarsky, Sandee (February 5, 2016). "Levana's Meal Replacements". New York Jewish Week.

- ^ Divola, Barry. "The real Seinfeld diner in New York: Inside Tom's Restaurant", The Sydney Morning Herald, February 23, 2016. Accessed December 29, 2023. "But Tom's, which has been in business on the corner of Broadway and W112th Street in Morningside Heights on the Upper West Side since the late 1940s, is different for one very big reason. It was the Seinfeld diner. An exterior shot featuring its distinctive signage was used in any episode where Jerry, George, Elaine and Kramer would meet to drink coffee, order a big salad and exchange banter about nothing."

- ^ "Find Your Precinct and Sector - NYPD". www.nyc.gov. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ "NYPD – 20th Precinct". www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "NYPD – 24th Precinct". www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "20th Precinct CompStat Report" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c "NYC Crime Map". www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ a b "Citywide Seven Major Felony Offenses 2000-2019" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York Police Department. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ a b "Citywide Seven Major Felony Offenses by Precinct 2000-2019" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York Police Department. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ "24th Precinct CompStat Report" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ "FDNY Firehouse Listing – Location of Firehouses and companies". NYC Open Data; Socrata. New York City Fire Department. September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 40/Ladder Company 35". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Ladder Company 25/Division 3/Collapse Rescue 1". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 74". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 76/Ladder Company 22/Battalion 11". FDNYtrucks.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Manhattan Hospital Listings". New York Hospitals. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Best Hospitals in New York, N.Y." U.S. News & World Report. July 26, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Midtown, New York City-Manhattan, New York Zip Code Boundary Map (NY)". United States Zip Code Boundary Map (USA). Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Ansonia". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Cathedral". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Columbus Circle". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Park West". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Planetarium". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Upper West Side – MN 07" (PDF). Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Upper West Side New York School Ratings and Reviews". Zillow. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 009 Sarah Anderson". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 075 Emily Dickinson". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 084 Lillian Weber". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 087 William Sherman". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 145, The Bloomingdale School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 163 Alfred E. Smith". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 165 Robert E. Simon". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 166 The Richard Rodgers School of The Arts and Technology". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "The Riverside School for Makers and Artists". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 199 Jessie Isador Straus". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 212 Midtown West". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 333 Manhattan School for Children". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 452". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. M811 - Mickey Mantle School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ a b "Special Music School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "The Anderson School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "J.H.S. 054 Booker T. Washington". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "Mott Hall II". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "M.S. 243 Center School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "M.S. M245 The Computer School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "M.S. M247 Dual Language Middle School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "M.S. 250 West Side Collaborative Middle School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "Lafayette Academy". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "MS 258 Community Action School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "West Prep Academy". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "Edward A. Reynolds West Side High School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "The Maxine Greene HS for Imaginative Inquiry". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "High School for Law, Advocacy and Community Justice". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "High School of Arts and Technology". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "Manhattan / Hunter Science High School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "Urban Assembly School for Media Studies, The". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "Frank McCourt High School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "Innovation Diploma Plus". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "The Global Learning Collaborative". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "The Urban Assembly School for Green Careers". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "About the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center". The New York Public Library. May 10, 1907. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "About the Bloomingdale Library". The New York Public Library. May 10, 1907. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "About the Riverside Library". The New York Public Library. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "About the St Agnes Library". The New York Public Library. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "The Church of St Paul the Apostle". www.stpaultheapostle.org. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "The Church of St Paul the Apostle". www.stpaultheapostle.org. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Redeemer". Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ "The Berrigans: Jail for the Christian Conscience". TIME. May 4, 1970. Archived from the original on March 28, 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Toibin, Colm (April 13, 2001). "MY MANHATTAN; Mais Non! Forte, Please! Ay-Yi-Yi!". The New York Times.

- ^ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ An Oral History of the Beastie Boys Archived March 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine New York magazine

- ^ http://www.angelfire.com/tx/COJACK/BeastieBoys/History.html [1] Liner notes from the Beastie Boys album Some Old Bullshit

- ^ "Tom's Diner". Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2015. Tom's Diner @ The Rusty Pipe

- ^ "Review: The Tale of the Allergist's Wife" Archived December 5, 2020, at the Wayback Machine by Phil Gallo, Playbill, June 27, 2002