Beaumaris, Victoria

| Beaumaris Melbourne, Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Watkins Bay viewed from Ricketts Point | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°58′59″S 145°02′36″E / 37.983°S 145.0434°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 13,947 (2021 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 2,682/km2 (6,950/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 3193 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 20 m (66 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 5.2 km2 (2.0 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 20 km (12 mi) from Melbourne | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Bayside | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Sandringham | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Goldstein | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

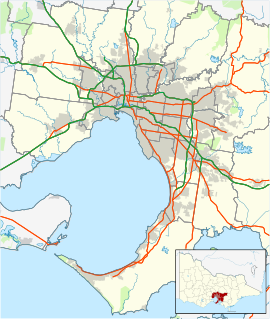

Beaumaris (/boʊˈmɒrəs/ bo-MORR-əs) is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 20 km south-east of Melbourne's Central Business District,[2] located within the City of Bayside local government area. Beaumaris recorded a population of 13,947 at the 2021 census.[1]

Beaumaris is located on Port Phillip Bay and is bounded by Reserve Road and Weatherall Road in the north, Charman Road in the east, the Port Phillip Bay foreshore in the south, and McGregor Avenue, Fifth Street, Keating Street, Iluka Street, Fairleigh Avenue and Royal Melbourne Golf Club in the west.

Geology

[edit]

The blunt V-shaped intrusion of land into the Bay that is spearheaded by Table Rock Point is referred to as the Beaumaris 'Peninsula'. The Beaumaris cliffs to the north east of Table Rock are formed by the steeply folded rock layers known as the Beaumaris Monocline, which is considered to be of Tertiary age overlying older structures.[3] These include the underlying Silurian rock known as the Fyansford formation above which is the 15 m thick darker Beaumaris Sandstone, overlain by yellowish Red Bluff Sandstone, as outcrops in the cliffs, ferruginised, with hard ironstone in the upper sections, extending to the platform, and as small reefs parallel to the coastline. A thin calcareous sandstone is overlain by fine sandy marl and sandstone with calcareous concretions. At the base of the sandstone is a thin gravelly bed that includes concretionary nodules of phosphate and iron of which detached nodules may be found around the cliff base.[3][4]

The Monocline can be seen where the cliffs of Beaumaris are locally parallel to the turnover of the monocline, which forms a drainage divide between the Gardners Creek-Dandenong Creeks systems and the Carrum Swamp.[5] Layers in the cliff are almost horizontal, but fold downward almost 30º toward the vertical south-easterly and out to sea.[6] Jagged remains of the strata can be seen off-shore at low tide from the cliff-top walk at the end of Wells Road.[7]

Behind Keefer's Fishermens Wharf the lower level of the cliffs is a fossil site of international significance.[8] Shells, sea urchins, crabs, foraminifera, remains of whales, sharks, rays and dolphins, and also birds and marsupials, dating back to the Late Miocene to Early Pliocene (12 to 6 million years ago) can be found, and have been the subject of a number of papers.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

History

[edit]Indigenous occupation

[edit]

The Bunurong (or Boon Wurrung) peoples of the Kulin nation lived along the Eastern coast of Port Philip Bay for over 20,000 years before white settlement.[17] Their mythology preserves the history of the flooding of Port Phillip Bay 10,000 years ago,[18] and its period of drying and retreat 2,800–1,000 years ago.[19] Visible evidence of their shell middens and hand-dug wells remain along the cliffs of Beaumaris,[20][21] but by the 1850s most withdrew to the Mordialloc Aboriginal Reserve established in 1852, and after the 1860s, to Coranderrk.

European settlement

[edit]

One of the first white settlers was James Bickford Moysey[22] in 1845,[23] who, along with several other local settlers had Welsh roots, and he gave the name 'Beaumaris' to his pastoral run after the Welsh Town of Beaumaris (Welsh: Biwmares) on the Isle of Anglesey in the Menai Strait, called 'beaux marais' by Norman-French builders of the castle there, a name which translates as "beautiful marshes". Moysey eventually purchased 32 hectares for his farm.[24] There is a monument on the foreshore opposite the hotel where Moysey had built a house.[25]

Beaumaris cemetery

[edit]The first Cheltenham settlers, Stephen and Mary Ann Charman, donated land in 1854 that was the first cemetery of the area, established in the churchyard of the small timber Wesleyan Church at the western corner of what is now Balcombe Road and Bickford Court.[26] There, two of the Charman's own babies were buried in 1855 and 1859. Soon reaching capacity, this small cemetery operated for only 11 years with the last known burial in 1866. Other faiths traveled to Brighton to bury their dead. The church building on the site was sold in 1893 and moved to Langwarrin and the land turned over to grazing. In 1954 the Moorabbin Council, faced with growing population and ramping land values, granted a permit to the Methodist Church to subdivide the land. Everest Le Page, Moorabbin Councillor and Cheltenham resident, believing that the previous burial sites may not have been relocated following the closure of the church, argued unsuccessfully against sub-division and seven lots of land were sold and houses built there. Researcher Shirley Joy was unable to find evidence in 1998 that the church burials at the site had been relocated prior to the subdivision and development of the land [27] Responding to her efforts Mayor of Bayside, Cr Graeme Disney, had a commemorative bronze plaque set into the footpath at the corner of Balcombe Road and Bickford Court, Beaumaris.[28]

Establishment of the suburb

[edit]Current day Beaumaris covers two early estates in the parish of Moorabbin developed by Josiah Holloway from 1852. Named Beaumaris Town and Beaumaris Estate after the Moysey holding, the lots comprising them were marketed by Mr. Holloway's suggesting that the railway was imminent and a canal would be built.[29] Advertising for an auction on 13 March 1876 of blocks of land at "Dalgety's Paddock" between Balcombe Road and the beach, Beaumaris, portion no. 48, Parish of Moorabbin, describes the area as "The Ramsgate of Victoria," after the seaside town in East Kent.[30]

A Beaumaris Post Office was opened on 1 March 1868, but was renamed Gipsy Village (now Sandringham) office at the end of that month.[31] The township developed slowly, with Beaumaris Hotel, the first shop and civic hall being built in the 1880s. Beaumaris Post Office did not reopen until 1925. In 1957, this was renamed Beaumaris South when a new Beaumaris office opened in the current location. In 1954, Cromer Post Office opened to the north of the suburb.[32]

The 'Great Southern' hotel was built in 1889 as a seaside resort, then in the 1920s, was renamed the Beaumaris Hotel.[33] The original structure survived in the Beaumaris bushfires of 1944, only to be extensively rebuilt and extended in 1950 as 'The Beaumaris'. In 2014, the hotel was converted into 58 apartments.[34]

Beaumaris Tram Company

[edit]

Horse tramway

[edit]

At the height of the Victorian land boom in 1887, the Brighton railway line was extended to Sandringham. Thomas Bent, Chairman of Moorabbin Shire Council, keen to stimulate development south of Sandringham sought and received permission to build two tramways from Sandringham station along the coast road to Beaumaris, and from there to Cheltenham railway station, with a branch from Beaumaris continuing down the coast road to Mordialloc; more than 15 kilometres of tramline in total.

The Shire Council contracted the Beaumaris Tramway Company (BTC) in February 1888 for a horse tramway with a 30-year operating lease. The Sandringham to Cheltenham route cost £20,000 and opened that Christmas. At the February 1891, half-yearly meeting of the Beaumaris Tramway Company Limited the chairman Mr. H. Byron Moore reported that a recent doubling of traffic was coupled to the increasing popularity of cheap rail return tickets to Sandringham issued by the Victorian Railways,[35][36] nearly 17,000 of which had been issued.[37] Holiday-makers were offered moonlight tram rides during summer that year[38] and artists of the Victorian Sketching Club used the service.[39] The Mordialloc branch line was never built, and after the land boom bubble burst in 1891, development beyond Black Rock ceased for several decades. Holiday traffic kept the business afloat until in 1912 the Beaumaris to Cheltenham section closed, and in 1914, the BTC ceased operation.

There are no remains of the line to be found, but it is remembered by the name of the suburban street that it once used; Tramway Parade, Beaumaris.

Electric trams

[edit]

Development from the first decade of the twentieth century of the area between Sandringham and Black Rock prompted formation of a public association to lobby for extension of the Sandringham railway that gained Parliamentary support in 1910, though it was vetoed over the high cost of land resumptions. In both 1913 and 1914, proposals were put forward for an electric tramway from Sandringham to Black Rock but using an inland route to preserve the visual amenity of the coastal reserves.[40] In November 1914, an Act enabled this tramway to be owned and operated by Victorian Railways, on standard gauge to cater for any future connection to the main Melbourne system.[41] The line, almost entirely double track, was opened on 10 March 1919 with a small three-road depot at Sandringham railway station yard connecting with the down track in Bay Street. Six crossbench cars with six trailers operated on the tramway, with Elwood Depot maintaining track and rolling stock, joined in 1921 by four new bogie tramcars.[42]

Beaumaris residents' lobbying for an extension of the Black Rock service was considered by the Parliamentary Standing Committee in 1916 and again in 1919, but it was not until 1925 that an agreement was struck between VR and Sandringham City Council for the latter to provide a £2,000 annual operating subsidy to the proposed extension for a period of five years. As a result, construction of the Beaumaris extension commenced, and the single-track line was opened on 1 September 1926. The line ran from the end of Bluff Road in Black Rock, along Ebden Avenue, Fourth Street, Haydens Road, Pacific Boulevard, Reserve Road, Holding Street, and to the end of Martin Street almost up to the intersection of Tramway Parade, where a switch allowed the tram to make the reverse trip.[43][44] As the anticipated residential development did not occur, the 'Bush Tramway', as it came to be known, ran at a heavy loss despite the £2,000 operating subsidy, and exactly five years after opening, the Beaumaris extension closed on 31 August 1931.[45] Until the 1960s when roads were surfaced, traces of the asphalt and timber foundations of the tramway remained in the centre of Holding Street.

Sea baths

[edit]

Sea baths were constructed in Beaumaris and used for more than thirty years from 1902 to 1934.

In the 1890s, there were proposals to build fenced and netted baths with changing facilities in the sea at Beaumaris, like those at Sandringham and Brighton Beach, and others at Mentone and Mordialloc which were operated by the Shire of Moorabbin.

Support for the idea came in 1896 from the proprietor of the Beaumaris Hotel Mrs. Finlay, who offered £20 per year for use of the baths by her boarders free of charge, and John Keys, the Shire Secretary and Engineer envisaged additional income to the council of £15 from its lease.[46] By August that year, Cr. Smith reported that residents would raise a subscription and requested that plans be drawn up and tenders called.[47] An alternative proposal was to use the hulk Hilaria floated off-shore to house the baths. That caused some dispute but came to nothing, delaying progress until 1902 when tenders were finally called for a conventional bath.

Charles Keefer was ultimately successful in his bid for £105 to build, with additional rooms, the structure planned for a site beneath the cliffs east of Beaumaris Hotel, and it was he who was accepted to lease the baths at a rent of £15. Charges were £1 per annum per person, or a monthly ticket of five shillings, while a single bath cost three pence. Keefer managed both the Beaumaris Baths and a boat hire facility operated from a jetty he constructed nearby until, on 30 November 1934, a storm destroyed the baths,[48] which were never rebuilt.[49] The same storm's destruction of bathing boxes appears in paintings by Beaumaris artist Clarice Beckett.[50]

Factory village

[edit]In 1939, Dunlop Rubber Company purchased 180 hectares of land in Beaumaris, intending to build a large factory and model village in an area bounded by Balcombe Rd., Beach Rd., Gibbs St. and Cromer Rd.[51] Plans were shelved a month later with the outbreak of World War II.

1944 bushfires

[edit]

In the midst of WW2 and a severe drought, came disastrous bushfires on 14 January 1944,[52][53] which killed 51 people across Victoria.[54][55] The maximum temperature in Melbourne that day was 39.5 °C with gusty hot northerly winds driving two fire fronts across the heavily wooded suburb.[56][53] The number of homes destroyed in sparsely populated Beaumaris was reported at between 63 and 100, leaving 'a square mile' burnt out, and 200 homeless.[56] Hundreds of volunteers, including many from the city, with fire brigades from neighbouring suburbs and soldiers who were trucked in, could not control the flames.[57] Householders and holidaymakers cut fire-breaks, but fire leapt every gap,[57] leaving 7 caravans and 5 cars gutted in the caravan park.[58] Scores of people sheltered in the sea for hours from fierce flames in the cliff-top ti-tree, with many suffering exposure as a result and some with severe burns also contracting pneumonia.[57][59]

Although everyone who had lost their homes had been provided with temporary accommodation by the Red Cross and Salvation Army, many in rooms, lounges and corridors of the Beaumaris Hotel that was one of the few buildings left standing,[60] more permanent accommodation was difficult to provide.[61] Damage estimated by the office of the Town Clerk at Sandringham at £50,000 (not including clothing, furniture and other personal effects lost) was done to buildings.[61] The Premier Albert Dunstan convened a special meeting of Cabinet to consider relief measures and, with Sandringham Lord Mayor Councillor Nettlefold, inaugurated a State-wide appeal.[56]

Road surfacing, 1960s

[edit]In 1949, architect Robin Boyd in a regular column in Melbourne's The Age noted that:

"Beaumaris has been described as the Cinderella suburb. It is young, beautiful and neglected, by its parent council. Its streets are narrow tracks twisting through thick scrub...A car or two bogs every day somewhere in this most attractive of all Melbourne's new suburbs.[62]

The appearance of the original 'tracks' were recorded in an album by W.L. Murrell, photographer and Hon. Librarian of the Beaumaris and District Historical Trust.[63] Most of the "ti-tree tracks" that roughly followed the street grid of Beaumaris remained unmade until the City of Sandringham realigned and surfaced them in asphalt between concrete kerbs in a campaign during 1961–67. The tree-clearing required was opposed by many residents,[64] but their protests were successful only in Point Avenue, which remained an unmade private road.[65][66]

Education

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (July 2024) |

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

-

Beaumaris Primary School

-

Beaumaris Secondary College

-

Stella Maris Primary

-

Stellia Maris Church next to the Primary School of the same name.

-

Beaumaris West primary school class of 1914

Elementary education for Beaumaris children in the mid-1800s was provided by the closest 'common school'; a private school started by Frederick and Fanny Meeres in 1855 in a single-room wooden dwelling near the Cheltenham Railway Station. The school was first named the Beaumaris Wesleyan School. In 1863, it became a public school under the control of the National Schools Board, and in 1864, Henry Wells, George Beazley, and Samuel Munby were appointed by the Board to the 'Beaumaris School' on its committee. A Church of England Cheltenham school had also been established on 1 October 1854 in an area 25 minutes walk away and east of Point Nepean Road and north of Centre Dandenong Road. Due to their proximity in 1869, it was to be amalgamated[67][68] with the 'Beaumaris' school, though the former raised religious objections.[69] The Meeres school was relocated onto Crown Land in Charman Road, Cheltenham and in 1872 renamed Beaumaris Common School No. 84. Amongst several others for works in the city and suburbs, the lowest tender at £1055 from Mr George Evans of Ballarat, was publicly accepted in November 1877 by the Education Department for the construction of a brick school at the current site.[70] There it continued as the 'Beaumaris' school until 1885, when it finally became State School No. 84 Cheltenham, the name it retains.

As population in Beaumaris increased so came demands that a school be established within the suburb, so that small children would not need to walk 3.6 km to Charman Road. Subsequently, in May 1915, Beaumaris State School, no.3899, was opened for 41 pupils in the old hall built in the heyday of the 1880s land boom and situated between Martin Street and Bodley Street on the site currently occupied by Beaumaris Bowls Club. The 432sq. metre brick and timber theatre hall had an upper circle and rooms below the stage. The first teacher, from May 1915, was Mrs Fairlie Taylor (née Aidie Lilian Fairlam).[71] It moved in 1917 to its current site in Dalgetty Road as the population of the school grew. Beaumaris North Primary School[72] first opened in 1959 followed by Stella Maris Primary School (Roman Catholic),[73] once attended by Member of the Victorian Legislative Assembly for Sandringham Brad Rowswell. Beaumaris High School, which opened in 1958, became the Beaumaris Campus of Sandringham College, catering to years 7–10, from 1988 until 2015. A new high school catering for years 7–12, Beaumaris Secondary College, was built on the same site at the corner of Reserve Road and Balcombe Road and opened in January 2018.[74] Beaumaris Primary School administration building and some of the classrooms were damaged by fire in 1994. Beaumaris Primary school was centre of a inquiry into Child Sexual abuse offences in the 1960 and 1970's.[75]

Transport

[edit]Major thoroughfares in Beaumaris include Balcombe Road, Reserve Road, Beach Road, Haydens Road and Charman Road.

Beaumaris is serviced regularly by bus routes to St Kilda, Dandenong, Moorabbin and Westfield Southland.

Beaumaris is accessible from the Frankston and Sandringham railway lines.

Ricketts Point

[edit]

The most prominent landmarks of this suburb are on its coastline, and include the Beaumaris Cliff, from Charman Road to Table Rock, which is of international importance as a site for marine and terrestrial fossils, and Ricketts Point, which adjoins a 115 hectare Marine Sanctuary and popular beach area. The coastal waters from Table Rock Point in Beaumaris to Quiet Corner in Black Rock and approximately 500 metres to seaward formally became the Ricketts Point Marine Sanctuary under state legislation passed in June 2002.[citation needed]

Marine Care Ricketts Point Inc., a volunteer organisation concerned with the preservation of the marine sanctuary, is active at Ricketts Point.

Beaumaris Conservation Society Inc. was founded in 1953 as the Beaumaris Tree Preservation Society[64][76] and has been active since then in championing the conservation of the substantial amount of remaining indigenous vegetation in Beaumaris and its other significant environmental qualities. It is campaigning against a proposal for a large private marina proposed for the Beaumaris Bay Fossil Site.

Ricketts Point is also home to the Beaumaris Life Saving Club,[77] which holds yearly Life Saving Carnivals in the summer.

People

[edit]Artists

[edit]

Heidelberg school

[edit]

From the late 19th century Beaumaris and its coastal scenery attracted artists. Near Ricketts Point, there is a monument commemorating the first encounter of Arthur Streeton and Heidelberg school artists Tom Roberts,[78] and Fred McCubbin who rented a house over the summer of 1886/7. McCubbin later painted A ti-tree glade there in 1890.[79] Their associate, Charles Conder also painted idyllic scenes on the beach at Rickett's Point before he left for Europe in 1890. These paintings of Beaumaris are featured on plaques at the sites which they depict in the City of Bayside Coastal Art Trail.

Barbizon

[edit]Michael O'Connell (1898–1976), a British soldier returned from the Western Front, between 1924 and 1926 built Barbizon (named after the French art school), on a bush block in Tramway Parade near Beach Road. The house was constructed from hand made concrete blocks on a simple cruciform plan and regarded by some as an early Modernist design.[80] It became a meeting place for Melbourne's alternative artists and designers including members of the Arts and Crafts Society. During the 1920s O'Connell focussed on School of Paris inspired textile design with his wife Ella Moody (1900–1981). Michael and Ella returned to England for a visit in 1937 but with the outbreak of war remained there and never returned to Australia. Barbizon was destroyed by the bushfire of 1944.[81]

Clarice Beckett

[edit]

Clarice Beckett (1887–1935) now highly regarded as an original Australian modernist,[82][83] moved with her elderly parents from Bendigo to St. Enoch's, 14 Dalgetty Rd., Beaumaris in 1919 to care for them in their failing health, a duty that severely limited her artistic endeavours so that she could only go out during the dawn and dusk to paint her landscapes. Nevertheless, her output was prodigious; she exhibited solo shows every year from 1923 to 1933 and with groups, mainly at Melbourne's Athenaeum Gallery, from 1918 to 1934. Many of her works depict still recognisable places along the coast as well as everyday 1920s suburban street scenes. While painting the wild sea off Beaumaris during a big storm in 1935, Beckett developed pneumonia and died four days later in Sandringham hospital, at age 48.[84] In the municipal council, the Beckett ward is named in her memory.

The Boyd family

[edit]In 1955 Arthur and Yvonne Boyd moved from Murrumbeena to Beaumaris before setting out in 1959 for a nine-year residency in England.[85] Robert Beck (1942-), the second son of Henry Hatton Beck and Lucy Beck (née Boyd), and his wife Margot (1948- ) set up a pottery at the Boyd's Surf Avenue house where his parents had returned from the UK to live.[86] The two couples worked closely together over this period, making a range of decorated wares and many of their most remarkable ceramic tiles.[87]

Architects and designers

[edit]

In the post-war period those returned from the military purchased land in the area, and after the bushfires there was much demand for new housing. Eric Lyon noted over 50 architects living in Beaumaris in the 1950s and a 1956 publication from the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects attributed to Robin Boyd the statement that Beaumaris had "the greatest concentration of interesting houses in the metropolitan area". Some of the earliest homes by Australia's best known architects are in Beaumaris: Grounds Romberg & Boyd, Peter McIntyre, Neil Clerehan, Chancellor and Patrick, Yunken Freeman, John Baird, Mockridge Stahle Mitchell, McGlashan Everist, Anatol Kagan, David Godsell and Peter Carmichael amongst others.[23]

In that immediate post-war period modest architect-designed timber dwellings, and 'beach houses,' were erected in Beaumaris which have come to be styled collectively "Beaumaris Modern".[23] With rectilinear, box-like volumes and typically small-scale, they were usually single-storey, of light construction on a minimalist plan, with flat or raking roofs, broad eaves supported on timber beams left visible in interiors, and with painted fascias. Timber cladding between brick pylons or planar walls, left space for Mondrian-esque bays of timber-framed, often full-height windows or a Stegbar Window Wall of Boyd design. Garages were incorporated into the structure (often half-basement) or were in the form of simple, attached flat-roofed carports. Surrounding gardens in the fast-draining sandy soil were of natives plants amongst existing ti-tree, gums and banksia.

Some were built by designers while in the course of their architecture degrees, such as the single-storey gable-roofed weatherboard house at 10 Hardinge Street, Beaumaris, attributed to David Brunton, Bernard Joyce and John Thornes-Lilly, but mostly the work of Brunton, who erected the house for his own use.

Beaumaris houses often incorporate bold experimentation in materials, forms and structural systems, such as Peter McIntyre's bowstring truss houses, influences of the Prairie School style of Frank Lloyd Wright and his contemporaries, extending to the 1970s in early examples of dwellings in the Brutalist style characterised by chunky forms with bold diagonal elements and raw concrete finishes first used in civic and institutional buildings in Australia from the mid-1960s, and applied to domestic architecture such as the award-winning Leonard French House in Alfred Street, Beaumaris. A long-time resident of Beaumaris, David Godsell was responsible for a number of buildings in the City of Bayside, the most important being Godsell's own 1960 house at 491 Balcombe Road, Beaumaris,[88] a multi-level Wrightian composition now included on the heritage overlay.[89] He also designed several buildings that were never built, including a remarkable Wright-influenced clubhouse for the Black Rock Yacht Club and a star-shaped Beaumaris house with a hexagonal module. Though, like many modernist homes in the district, several of his houses have been demolished since, surviving examples are simpler, more minimalist designs with planar face brick walls and floating flat roofs. Only the Grant House, 14 Pasedena Ave Beaumaris; the Godsell House, Balcombe Rd, Beaumaris; and the Johnson House, 451 Beach Rd Beaumaris, are under heritage protection.[90]

The Norman Edward Brotchie (1929–1991) pharmacy designed in the 1950s by architect Peter McIntyre featured boldly distinctive floor-to-ceiling coloured tile murals. The design by an unknown artist of overlapping cubist apothecary jars and bottles in yellow, brick-red, yellow and black covered sides of the facade and the interior walls of the premises at the southwest corner of Keys Street, Beaumaris. They were demolished during renovations in 2007.[23]

Significant mid-century industrial design and fittings emerged from Beaumaris in the same period; Donald Brown's aluminium BECO (a.k.a. Brown Evans and Co.) light fittings[91] featured in many houses (particularly those by Robin Boyd) in the 1950s and 60's,[92] while the designer of the famous Planet lamp Bill Iggulden, was a resident of Beaumaris.[23][93]

Beaumaris Art Group

[edit]In 1953, when Beaumaris still retained a village character, a small band of resident artist friends, including painter Inez Hutchinson (1890–1970),[94] sculptor Joan Macrae (1918–2017)[95] and ceramicist Betty Jennings staged an exhibition[96] which led to their establishing the Beaumaris Art Group, a not-for-profit organisation, later that year.

An exhibition in 1961 of five female artists including June Stephenson, Sue McDougall, Grace Somerville, Margaret Dredge[97] and Inez Green raised funds for the Art Group.[98] They continued to meet and exhibit at the Beaumaris State School,[99] before purchasing land and building studios in 1965 designed by local architect C. Bricknell at 84–98 Reserve Rd, which were opened by director of the National Gallery of Victoria, Dr. Eric Westbrook, who also launched the Inez Hutchinson awards in 1966.[100][101] Further structural additions by John Thompson were added in 1975/76.[102][103][104][23] Current President is Cate Rayson.[105]

Since 2016 Council and the BAG committee had discussed redevelopment of the BAG Studios in regard to safety and spatial requirements and a decision to demolish the building was made in May 2019. Community and heritage concerns caused this proposal to be rescinded in February 2020. A heritage report was commissioned in late 2019 as part of the ‘Mid-Century Modern Heritage Study—Council-owned Places’ (the ‘Heritage Study’) in which 8 Council-owned, mid-twentieth-century buildings were assessed for their heritage potential. It concluded that the BAG building was sound and demolition should be avoided.[106]

Galleries

[edit]Beaumaris Art Group houses a small gallery and display cases in its premises in which it displays its annual shows, open days and work by members.[107] In the 1950s before construction of its own quarters in 1965, its first annual exhibitions were held at the State School.[108][109]

Clive Parry Galleries,[110] managed by Russell. K. Davis, operated from 1966[111] until 1979 at 468 Beach Road, near the junction of Keys St., and exhibited paintings, drawings, textiles,[112] woodcraft,[113][114] ceramics,[115][116][117][118][119] jewellery,[120] and graphics[121] by artists including Margaret Dredge, Robert Grieve, Wesley Penberthy, Mac Betts,[122] Kathleen Boyle,[123][124] Colin Browne,[125] Ian Armstrong, Noel Counihan, Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz, David Dridan, Judi Elliot,[126] Vic Greenaway,[115][116][127][128] Tim Guthrie, Ann Graham,[129] Erica McGilchrist,[130] Warren Breninger, Max Middleton,[131] Millan Todd,[132] Douglas Stubbs,[133] Alfred Calkoen,[134] Lynne Cooke, Peter Glass,[135] Noela Hjorth, Bruno Leti, Charles Billich, Barbara Brash, Dorothy Braund, Murray Champion,[136] Peter Jacobs,[137] Marcella Hempel,[112] Kevin Lincoln,[138] Judy Lorraine,[139] Mary MacQueen, Helen Maudsley, Jason Monet,[140] Tim Moorhead,[141] Victor O'Connor, Elizabeth Prior,[142] Anne Judell, Paul King,[143] Nornie Gude, Norman Lindsay, Ailsa O'Connor, Jack Courier, Alan Sumner, Howard Arkley, Alan Watt,[117] Tina Wentcher[144] and William Dargie.[145] In June 1975, 1976 and 1977 it hosted the Inez Hutchinson Award presented by the Beaumaris Art Group.[146][147][100]

Other venues more recently have included the Ricketts Point Tea House[148]

Creative professionals

[edit]Beside architects, other creative professionals who were residents of Beaumaris include fashion designers Sally Brown, Linda Jackson, Prue Acton and Geoff Bade; architect and historian Mary Turner Shaw; graphic designers Frank Eidlitz and Brian Sadgrove; flag designer and canvas goods manufacturer Ivor William Evans (1887–1960);[149] journalist and nature writer Donald Alaster Macdonald (1859?–1932) whose memorial is in Donald MacDonald reserve, and whose ideas were continued in 1953 when the Beaumaris Tree Preservation Society (now Beaumaris Conservation Society) was formed to conserve bushland against accelerating land clearances for housing and to encourage planting of indigenous vegetation.[150] Musicians include Colin Hay,[23] and Brett and Sally Iggulden (children of Bill Iggulden who designed the Series K Planet Lamp in 1962)[151] who were founders and members, with others from the district, of The Red Onion Jazz Band in the 1960s.[152]

Notable residents

[edit]- Christine Abrahams, director of eponymous gallery in Richmond lived at 372 Beach Road, designed in 1961 by noted Melbourne architect Arthur Russell, and next door to a block owned by Arthur Boyd[153]

- Prue Acton, fashion designer

- Effie Baker, photographer and advocate of the Baha’i faith

- Clarice Beckett lived with her parents at St. Enoch's, 14 Dalgetty Road and painted many landscapes of Beaumaris.[83]

- Ivor Treharne Birtwistle, journalist[154]

- Holly Bowles and Bianca Jones, two victims of the Laos methanol poisoning incident in November 2024.[155][156][157]

- Arthur and Yvonne Boyd, artists

- Ivor William Evans, flag designer and canvas goods manufacturer[158]

- Sir William Fry, politician

- Leonard French, artist

- Hal Gye, artist

- William John Harris, school principal and palaeontologist[159]

- Colin Hay, musician, actor

- Rex Hunt, television personality

- Linda Jackson, fashion designer

- Hugh Gemmell Lamb-Smith, Australian educator who landed at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915, and son of former President of the Moorabbin Shire Council, was born at Mrs Ricketts' Dinas Bran, in Wells Road, Beaumaris (then part of "Cheltenham") on 31 March 1889.

- Donald Alaster Macdonald, naturalist and journalist

- Photojournalist J. Brian McArdle, editor of Walkabout magazine.

- Michael O'Connell, artist

- Owen Phillips, army general

- Bruce Ruxton, president of the Victorian branch of the RSL

- Brian Sadgrove, designer[160]

- Mollie Shaw, architect and historian

- Len Stretton, judge and Royal Commissioner

- Saxil Tuxen, surveyor and town planner[161]

Demographics

[edit]At the 2021 Australian census, the suburb of Beaumaris recorded a population of 13,947 people. Of these 48.0% were male and 52.0% were female. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people made up 0.2% of the population:[162]

- Age distribution: Residents tend to be somewhat older than the country overall. The median age was 48 years, compared to the national median of 38 years. In Beaumaris in 2021 compared to Australia, there was a higher proportion of people in the younger age groups (0 to 17 years) as well as a higher proportion of people in the older age groups (60+ years). Overall, 25.5% of the population was aged between 0 and 19, and 29.5% were aged 60 years and over, compared with 23.6% and 23% respectively for Australia.

- Education: 41.5% of the population of Beaumaris hold a Bachelor or Higher degree compared to 26.3% across Australia. The number in 2021 with no qualification (0.1%) was smaller than the national (0.8%). A larger percentage of persons had Advanced Diploma or Diplomas (11.4% compared to 9.4% nationally), and a smaller percentage of persons held Vocational qualifications. Of all people attending educational institutions, 18% were secondary students in Independent schools compared to 13.3% attending Government schools.

- Ethnic diversity: In 2021 a smaller proportion of the population in Beaumaris, 26.4%, was recorded as born overseas compared to 33.1% being the national average, with the major differences between the countries of birth of the population in Beaumaris and Australia being a larger percentage of people born in England (7.2% compared to 3.6%), and a smaller percentage of people born in China (1.4% compared to 2.2%), though the latter had grown by 64 persons between 2011 and 2016. In 2021 in Beaumaris 86.9%, a higher proportion compared to 72% in Australia as a whole, spoke English only. In 13.6% of households another language other than English was used compared with 24.8% for all Australian households. In the whole Beaumaris population Greek (1.6%) was the most common other language spoken at home, followed by Mandarin (1.7%), German (0.9%) and Italian (1.4%)

- Finances: The median household weekly income was $2,626, compared to the national median of $1,746. This difference is also reflected in real estate, with the median mortgage payment being $3,000 per month, compared to the national median of $1,863.

- Transport: On the day of the Census, 2% of employed people travelled to work on public transport, and 42% by car (either as driver or as passenger), while nationally the percentages were a higher 4.6% using public transport and 57.8% using cars.

- Housing: The great majority (78.9%) of occupied dwellings were separate houses, 15.5% were semi-detached, 5.1% were flats, units or apartments and 0.6% were other dwellings. 79.4% of all dwellings were family homes, while 19.8% held sole occupants.

- Religion: In Australia, the biggest cohort people in the 2021 census at 38.4%, and growing, reported their religion as 'None,' and the percentage in Beaumaris was higher still, at 45.3%. 21.4% of Beaumaris residents are Catholic, compared to 20% across Australia, 13.7% (compared to 9.8%) are Anglican, and 3.5% are Eastern Orthodox compared to 2.1% nationally.

Politics

[edit]Federal government

[edit]The Division of Goldstein is an Australian Electoral Division in Victoria. The division was created in 1984, when the former Division of Balaclava was abolished. It comprises the bayside suburbs Beaumaris, Bentleigh, Brighton, Caulfield South, Cheltenham (part), Gardenvale and Sandringham. The division is named after early feminist parliamentary candidate Vida Goldstein. It is represented by Independent Zoe Daniel.

State government

[edit]Beaumaris is in the Electoral district of Sandringham, one of the electoral districts of Victoria, Australia, for the Victorian Legislative Assembly, with Black Rock and Sandringham, and parts of Cheltenham, Hampton, Highett, and Mentone.

Since the seat was created in 1955, it has been held by the Liberal Party, except for the period 1982-5 when it was held by the Labor Party. The seat is currently held by Brad Rowswell of the Liberal Party.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | Brad Rowswell | 18,783 | 46.4 | +3.8 | |

| Labor | Bettina Prescott | 10,426 | 25.7 | −7.4 | |

| Greens | Alysia Regan | 5,949 | 14.7 | +6.5 | |

| Independent | Clarke Martin | 2,800 | 6.9 | −1.6 | |

| Animal Justice | Barbara Eppingstall | 976 | 2.4 | −0.8 | |

| Democratic Labour | Karla Zmegac | 749 | 1.9 | −1.0 | |

| Family First | Jill Chalmers | 572 | 1.8 | +1.8 | |

| Independent | Rodney Campbell | 115 | 0.3 | +0.3 | |

| Total formal votes | 40,512 | 96.0 | +1.3 | ||

| Informal votes | 1,699 | 4.0 | −0.8 | ||

| Turnout | 42,211 | 91.2 | +2.2 | ||

| Two-party-preferred result | |||||

| Liberal | Brad Rowswell | 22,399 | 55.2 | +4.8 | |

| Labor | Bettina Prescott | 18,216 | 44.1 | −4.8 | |

| Liberal hold | Swing | +4.8 | |||

Results are not final. Last updated at 1:25 on 12 December 2022.

Local government

[edit]Beaumaris is in the local government area of the City of Bayside and occupies two of its wards since redistributions in 2008; Ebden (west and north),[164] and Beckett (south and east).[165] Current councillors elected October 2020 are Clarke Martin (Beckett ward) and Lawrence Evans (Ebden ward) who is Mayor. Both are Independents.

See also

[edit]- City of Moorabbin – Parts of Beaumaris were previously within this former local government area.

- City of Mordialloc – Parts of Beaumaris were previously within this former local government area.

- City of Sandringham – Parts of Beaumaris were previously within this former local government area.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Beaumaris (Vic.) (Suburbs and Localities)". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ "Postcode for Beaumaris, Victoria". postcodes-australia.com.

- ^ a b Singleton, F.A. (1941). The Tertiary geology of Australia. Proc. R. Soc. Vict., 53, 1–125.

- ^ CARTER, A. Phosphatic nodule beds in Victoria and the late Miocene–Pliocene eustatic event. Nature 276, 258–259 (1978) doi:10.1038/276258a0

- ^ King, P.R., Cochrane, R.M. & Cooney, A.M. (1987). Significant geological features along the coast in the City of Sandringham. Unpub. rep. geol. Surv. Vict., 1987/35

- ^ Neilson, J. L.; Peck, W. A.; Olds, R. J.; Seddon, K. D., eds. (1992). Engineering geology of Melbourne. A. A. Balkema. ISBN 978-0-203-75741-3.

- ^ "Beaumaris monocline" (PDF). Coastal guide books. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Beaumaris Bay Fossil Site Beach Road, Beaumaris, Victoria, Australia: Register of National Estate. (1999). Australia: Australian Heritage Database.

- ^ Chapman, T.S. & Cudmore, F.A. (1924). New or little known fossils in the National Museum. Proc. R. Soc. Vict., 36, 107–162.

- ^ Gill, E.D. (1957). The stratigraphical occurrence and palaeoecology of some Australian Tertiary Marsupials. Mem. Nat. Mus. Vict., 21, 135–203.

- ^ Woodburne, M.O. (1969). A lower mandible of Zumogaturus gilli from the Sandringham Sands, Beaumaris, Victoria, Australia. Mem. Nat. Mus. Vict., 29, 29–39.

- ^ Wilkinson, H.E. (1969). Description of an upper Miocene albatross from Beaumaris, Victoria, Australia, and a review of fossil Diomedeidae. Mem. Nat. Mus. Vict., 29, 41–51.

- ^ Simpson, G.G. (1970). Miocene Penguins from Victoria, Australia and Chubut, Argentina. Mem. Nat. Mus. Vict., 31, 17–23

- ^ Ter, P. C., & Buckeridge, J. S. J. (2012). 'Ophiomorpha Beaumarisensis Isp. Nov., A Trace Fossil from the Late Neogene Beaumaris Sanstone is the Burrow of a Thalassinidean Lobster'. In Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria, 124(2), 223.

- ^ Fitzgerald, E. M., & Kool, L. (2015). The first fossil sea turtles (Testudines: Cheloniidae) from the Cenozoic of Australia. Alcheringa: an Australasian Journal of Palaeontology, 39(1), 142–148.

- ^ Megirian, Dirk, Gavin Prideaux, Peter Murray, and Neil Smit. "An Australian Land Mammal Age Biochronological Scheme." Paleobiology 36.4 (2010): 658–71. Web.

- ^ Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Bunurong (VIC)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- ^ "Boon Wurrung: The Filling of the Bay – The Time of Chaos – Nyernila". Culture Victoria. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ G. R. Holdgate, B. Wagstaff & S. J. Gallagher (2011) Did Port Phillip Bay nearly dry up between ~2800 and 1000 cal. yr BP? Bay floor channelling evidence, seismic and core dating, Australian Journal of Earth Sciences, 58:2, 157–175, DOI: 10.1080/08120099.2011.546429

- ^ Massola, Aldo (1959). The native water wells of Beaumaris and Black Rock. OCLC 815509348.

- ^ Brooks, A. E. (1960). The Aboriginal Well at Beaumaris. (n.p.): (n.p.).

- ^ "[n.d.]. James Bickford Moysey, 1809–1889". Item held by Bayside Library Service. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Austin, Fiona; Reeves, Simon Andrew; Alexander, Alison; Shelton, Jack; Swalwell, Derek; Goad, Philip (2018). Beaumaris modern : modernist homes in Beaumaris. Melbourne Books. ISBN 978-1-925556-40-7.

- ^ "Beaumaris | Victorian Places". Victorianplaces.com.au. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Pioneer Settlers | Kingston Local History". Localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ "Beaumaris Cemetery". Beaumaris Conservation Society. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ Joy, Shirley M (1995). The search for the Beaumaris Cemetery, Victoria 1855-1865: the Wesleyan burial ground in the parish of Moorabbin. Sandringham, Vic.: S.M. Joy. ISBN 978-0-646-26318-2. OCLC 38396561.

- ^ "The Beaumaris Cemetery | Kingston Local History". localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Kingston Local History, Josiah Holloway, archived from the original on 21 November 2008, retrieved 22 October 2008

- ^ Plan of Dalgety's Paddock at Rickards Point below Brighton, 1876, retrieved 21 November 2021

- ^ "NOTES AND NEWS". The Leader. Vol. XV, no. 639. Victoria, Australia. 28 March 1868. p. 5. Retrieved 15 November 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Phoenix Auctions History, Post Office List, retrieved 27 January 2021

- ^ "Beaumaris Hotel c.1910". State Library Victoria. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "New Beaumaris Hotel conversion pays homage to site's storied history". Propertyobserver.com.au. 23 February 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Frost, D. (2006). A short history of the Victorian railways trams : St. Kilda – Brighton – Sandringham – Black Rock – Beaumaris / by David Frost. Nunawading, Vic.: Tramway Publications.

- ^ Trips by Rail from Melbourne: To Sandringham, Mentone, Mordialloc, Frankston, Mornington, Beaumaris on the Sea. (1908). Australia: (n.p.).

- ^ "The Beaumaris Tramway Company Limited". The Argus. No. 13, 926. Victoria, Australia. 11 February 1891. p. 7. Retrieved 9 October 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 21, 1891". Argus. 21 January 1891. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ "Promenade Concert At The Exhibition". Age. 21 December 1891. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ Marshall-Wood, Leon (1966), The Brighton electric line ([3rd ed. rev. and enl.] ed.), Traction Publications, retrieved 15 October 2019

- ^ Harrigan, Leo J; Victorian Railways. Public Relations and Betterment Board (1962), Victorian railways to '62, Victorian Railways Public Relations and Betterment Board, retrieved 15 October 2019

- ^ Budd, Dale; Cross, N. E. (Norman E.); Wilson, Randall, 1951– (1993), Destination city : Melbourne's electric trams (5th ed.), Transit Australia Publishing, ISBN 978-0-909459-17-8

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Marshall-Wood, Leon. "The Sandringham–Black Rock–Beaumaris Tramway, from 'The Brighton Electric Line'".

- ^ Marshall-Wood, Leon; Australian Electric Traction Association (1956), The Brighton electric line, Traction Publications, retrieved 15 November 2019

- ^ "Beaumaris Tram Company". Kingston Local History. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ Engineer's Report to Council, Minute Book, Shire of Moorabbin, 3 February 1896

- ^ Minute Book, Shire of Moorabbin, 3 August 1896, page 31

- ^ "REPAIRS TO BATHS". The Herald. No. 17, 964. Victoria, Australia. 11 December 1934. p. 7. Retrieved 15 November 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Beaumaris Baths, Kingston Local History". localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "Clarice Beckett, Boatsheds in the storm, 1934, oil on board, 17.6 x 22.6cm". Niagara Galleries.

- ^ "1945 Rydges Journal contained Dunlop Rubber Company's plan for Beaumaris village" (PDF). Beaumaris Conservation Society. 1945. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Barrow GJ (14 January 1944). "A survey of houses affected in the Beaumaris fire". Journal of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. 18 (1).

- ^ a b "The Beaumaris Bushfires of 1944 | Kingston Local History". localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ "20 Dead, Missing in Mounting Bushfire Deathroll". The Sun. No. 10, 616 (LATE FINAL EXTRA ed.). New South Wales, Australia. 15 January 1944. p. 1. Retrieved 24 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "VICTORIAN BUSHFIRE DISASTERS". The Herald. No. 20, 800. Victoria, Australia. 15 January 1944. p. 1. Retrieved 24 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c "Tents Alongside Ruins". The Mail. Vol. 32, no. 1, 651. Adelaide. 15 January 1944. p. 3. Retrieved 24 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c "Thousands Dash in Sea To Escape Vic. Bushfire". The Sun. No. 10, 615 (LATE FINAL EXTRA ed.). New South Wales, Australia. 14 January 1944. p. 2. Retrieved 24 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Bushfire Sweeps Through Beach Caravan Park". The News. Vol. 42, no. 6, 386. Adelaide. 17 January 1944. p. 1. Retrieved 24 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.|

- ^ "BUSHFIRE DEATH ROLL NOW AT LEAST 20". Truth. No. 2819. New South Wales, Australia. 16 January 1944. p. 1. Retrieved 24 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Hotel as refuge for fire victims". The Daily Telegraph. Vol. V, no. 10. New South Wales, Australia. 16 January 1944. p. 3. Retrieved 24 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "£50,000 Damage at Beaumaris". Weekly Times. No. 3892. Victoria, Australia. 19 January 1944. p. 5. Retrieved 24 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Cinderella suburb". The Age. No. 29430. Victoria, Australia. 24 August 1949. p. 6. Retrieved 5 September 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "W.L. Murrell, Hon. Librarian Beaumaris and District Historical Trust album, black covers, title on front cover "Beaumaris. 1961–67. Roads and Streets". Note on front cover: The "Teatree Tracks" in the City of Sandringham shown in this collection have all been "made" into modern, bitumen-and-concrete roads within the last six years. ie. by the end of 1967". search.slv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ a b "'BEAU – MARIS – OR BARE – MARIS?': Early pamphlet by the Beaumaris Tree Preservation Society urging retention of existing vegetation" (PDF). Beaumaris Conservation Society. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "Memories of Point Avenue, Beaumaris". The Logical Place. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Tim Harding, 'Memories of Point Avenue, Beaumaris'. In Sandringham & District Historical Society Newsletter, February 2019

- ^ "DEPUTATIONS (THIS DAY)". The Herald. No. 7205. Victoria, Australia. 28 January 1869. p. 2. Retrieved 15 November 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "BEAUMARIS AND CHELTENHAM COMMON SCHOOLS". The Age. No. 4444. Victoria, Australia. 29 January 1869. p. 3. Retrieved 15 November 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Beginnings of Cheltenham No84 | Kingston Local History". localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "MELBOURNE". Geelong Advertiser. No. 9, 481. Victoria, Australia. 28 November 1877. p. 4. Retrieved 16 November 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "BEAUMARIS". Moorabbin News. No. 735. Victoria, Australia. 27 January 1917. p. 4. Retrieved 15 November 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "History". BNPS. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Stella Maris Catholic Primary School | Beaumaris". smbeaumaris.catholic.edu.au. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Beaumaris Secondary College | Victorian School Building Authority". Schoolbuildings.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Jackson, Russell (27 February 2024). "'The truth needs to be told'". ABC News (Australia). Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ "SLAUGHTER EVERY SPRINGTIME". The Argus. No. 33, 422. Melbourne. 16 October 1953. p. 15. Retrieved 5 September 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Beaumaris Life Saving Club". Beaumaris Life Saving Club. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Croll, Robert Henderson; Roberts, Tom, 1856-1931 (1935), Tom Roberts : father of Australian landscape painting, Robertson & Mullens limited, p. 71, retrieved 22 November 2024

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ McCubbin, Frederick (1890). "A Ti-Tree Glade". Art Gallery of South Australia.

- ^ "The lost modernist of design". Theaustralian.com.au. 23 November 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ McPhee, John, "O'Connell, Michael William (1898–1976)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 24 August 2019

- ^ Clarice Beckett; Rosalind Hollinrake; Ian Potter Museum of Art (1999). Clarice Beckett: politically incorrect. Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne. ISBN 9780734015938.

- ^ a b Beckett, Clarice (2021). The present moment : the art of Clarice Beckett. Tracey Lock, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide Festival). Adelaide. ISBN 978-1-921668-46-3. OCLC 1244825369.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Beckett art joins Misty Moderns in Langwarrin" by Teresa Murphy, Hastings Leader, 12 November 2009

- ^ Niall, Brenda (2002), The Boyds : a family biography, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne University Press, ISBN 978-0-522-84871-7

- ^ "Duet in ceramics". The Canberra Times. Vol. 44, no. 12, 560. 4 March 1970. p. 20. Retrieved 5 September 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "BECK, Henry Hatton, aka HATTON-BECK – Trove List". Retrieved 25 August 2019 – via Trove.

- ^ "Godsell House by David Godsell - Feature - Mid-Century Architecture - VIC". The Local Project. 25 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Wixted, David; Reeves, Simon (11 May 2008). "City of Bayside Inter-War & Post-War Heritage Study, Volume 2" (PDF). City of Bayside. The City of Bayside & heritage ALLIANCE. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 November 2021.

- ^ Edgar, Ray (22 August 2017). "Online advocates fight to save Melbourne's modernist masterpieces". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Works | NGV | View Work". Ngv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "BECO :: biography at :: at Design and Art Australia Online". Daao.org.au. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Iggulden, Bill; Planet Lighting (1962), Series K desk lamp, retrieved 25 November 2021

- ^ Hutchinson, Inez (1949). "Green Hill, watercolour on cream paper; 20.0 x 28.5 cm. State Library of Victoria. Gift; Mr Jim and Dr. Helen Alexander; Jim Alexander Collection of Australian Women Artists". State Library Victoria. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Obituary". Sculpere Newsletter. 30 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "ART NOTES". The Age. No. 31, 009. Victoria, Australia. 21 September 1954. p. 2. Retrieved 25 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Not the usual Book Club Story: the Margaret Dredge retrospective & the workings of Australia art historiography". ProQuest 1383036408.

- ^ "Beaumaris Art Group Studios : Heritage Assessment" (PDF). S3.ap-southeast-2.amazonawc.com. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Art show in Beaumaris". The Herald. No. 24, 127. Victoria, Australia. 24 September 1954. p. 25. Retrieved 25 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Macdonald, Alix (22 August 1977). "crafting an art group". The Age. p. 16.

- ^ "Around the Suburbs : Art Award". The Age. 25 March 1966. p. 12.

- ^ GML Heritage Victoria Pty Ltd (27 July 2020). "Beaumaris Art Group Studios Heritage Assessment Draft Report Report prepared for Bayside City Council" (PDF). Context. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Beaumaris Art Group Studios". Beaumaris Art Group Studios. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ McCulloch, Alan; McCulloch, Susan (1994). The encyclopedia of Australian art (3rd. / revised and updated by Susan McCulloch ed.). Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86373-315-1.

- ^ "Meet the Beaumaris Art Group committee". Beaumaris Art Group. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ GML Heritage Victoria Pty Ltd (27 July 2020). "Beaumaris Art Group Studios: Heritage Assessment: Draft Report Report prepared for Bayside City Council" (PDF). Context. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "EG : art & craft". The Age. 20 March 1998. p. 63.

- ^ Sayers, Stuart (29 September 1956). "Exhibition". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ "Dog Fight...and Art". The Age. 1 October 1956. p. 2.

- ^ Childs, Kevin (25 November 1977). "Inside Melbourne's art world". The Age. p. 55.

- ^ "Advertisement". The Age. 10 September 1966. p. 23.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Ted (9 November 1976). "Tasteful weaving of skills". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ Greenwood, Ted (30 November 1976). "Craft : Master in clay new to glass". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ Greenwood, Ted (31 October 1978). "Working with a respect for materials". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Ted (19 October 1976). "Ceramic artists find new outlet". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Ted (26 March 1977). "Personal touch succeeds". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Ted (7 November 1977). "Porcelain has a message for us". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ "An Age Weekender guide to: Arts Victoria 78: Crafts". The Age. 3 February 1978. p. 35.

- ^ Greenwood, Ted (1 May 1978). "Craft : Exhibition explores eloquence". p. 2.

- ^ Greenwood, Ted (14 November 1977). "Craft". p. 2.

- ^ Gilchrist, Maureen (10 December 1975). "End-of-year feeling at galleries". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ Gilchrist, Maureen (16 June 1976). "Little to stimulate a jaded viewer". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ Byrne, Michele (29 August 1975). "'Frisco the place to study art". The Age. p. 16.

- ^ Gilchrist, Maureen (19 September 1975). "Prints move into the limelight". The Age. p. 4.

- ^ "Weekender : Craft : Ceramics". The Age. 9 September 1977. p. 37.

- ^ Greenwood, Ted (19 June 1978). "Ceramicist wears two hats". p. 2.

- ^ "Accent : Craft". The Age. 1 April 1977. p. 14.

- ^ Greenwood, Ted (13 November 1978). "Pottery can be happy and poetic". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ "Advertisement". The Age. 26 June 1976. p. 17.

- ^ "Paintings that wash". The Age. 5 November 1966. p. 6.

- ^ "Advertisement". The Age. 6 May 1967. p. 21.

- ^ "Advertisement". The Age. 8 June 1968. p. 14.

- ^ "Advertisement". The Age. 10 June 1967. p. 23.

- ^ "Now it's murals while you work". The Age. 29 September 1976. p. 17.

- ^ "Advertisement". The Age. 15 November 1975. p. 16.

- ^ Latrielle, Anne (13 July 1977). "Handbooks for the handyman". The Age. p. 16.

- ^ "Peter Jacobs (advertisement)". The Age. 6 March 1976. p. 20.

- ^ "Destroy obscene poster, rules SM". The Age. 3 October 1989. p. 11.

- ^ Greenwood, Ted (16 October 1978). "A marriage of form and sound". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ Eagle, Mary (20 September 1978). "Another look at drawing". The Age. p. 2.

- ^ "Living Out (This Easter) : Craft : Ceramics". The Age. 23 March 1978. p. 31.

- ^ "Advertisement". The Age. 2 April 1977. p. 14.

- ^ "Paul King silk screen prints (advertisement)". The Age. 18 June 1977. p. 18.

- ^ "Advertisement". The Age. 20 November 1976. p. 16.

- ^ Clive Parry Galleries; Clive Parry Galleries. Clive Parry Galleries: Australian Gallery File. OCLC 271079206.

- ^ "Advertisement". The Age. 7 June 1975. p. 19.

- ^ "Beaumaris Art Group". The Age. 5 June 1976. p. 19.

- ^ "Art & Craft : Margaret Gurney, exhibition of still-life, prints and drawings of beach themes, Ricketts Point Teahouse, Beach Rd, Beaumaris". The Age. 24 April 1998. p. 63.

- ^ Ritchie, John, "Evans, Ivor William (1887–1960)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 25 August 2019

- ^ Anderson, Hugh, "Macdonald, Donald Alaster (1859–1932)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 25 August 2019

- ^ "Series K desk lamp and electric light globe". collection.maas.museum. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "LISTEN HERE". Australian Women's Weekly (1933–1982). 6 May 1964. p. 10. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Brown, Jenny (13 February 2019). "Historic mid-century home on Beach Road, Beaumaris, is back on the market". Domain. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ Porter, Anne, "Birtwistle, Ivor Treharne (1892–1976)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 25 November 2021

- ^ Day, Lauren; Brown, Melissa; Vallance, Syan (19 November 2024). "Teens were on 'incredible adventure' through Asia before apparent methanol poisoning in Laos". ABC News (Australia). Archived from the original on 20 November 2024. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ Ore, Adeshola; Touma, Rafqa (21 November 2024). "Melbourne teen Bianca Jones dies in hospital after methanol poisoning in Laos". The Guardian (Australia). Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ Zervos, Cassie; Luff, Bryce (22 November 2024). "Laos methanol poisoning victim Holly Bowles dies in Thailand hospital a day after best friend Bianca Jones". Seven News. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ Ritchie, John, "Evans, Ivor William (1887–1960)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 25 November 2021

- ^ Darragh, Thomas A., "Harris, William John (1886–1957)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 25 November 2021

- ^ "Brian Sadgrove". Design Institute of Australia. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Australasian Urban History / Planning History Conference (10th : 2010 : University of Melbourne, Victoria); Nichols, David; Hurlimann, Anna; Mouat, Clare; Pascoe, Stephen (2010), Green fields, brown fields, new fields : proceedings of the 10th Australasian Urban History, Planning History conference, Melbourne University Custom Book Centre, p. 621, n34, ISBN 978-1-921775-07-9

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "2021 Beaumaris (Vic.), Census All persons QuickStats | Australian Bureau of Statistics". www.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ Sandringham District results, Victorian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "About the profile areas | Ebden Ward | profile.id". profile.id.com.au. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "About the profile areas | Beckett Ward | profile.id". profile.id.com.au. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

External links

[edit]- Bayside City Council Website

- Australian Places – Beaumaris

- Sandringham Secondary College

- Stella Maris Primary School

- Beaumaris Primary School

- Beaumaris Conservation Society Inc.

- Royal Melbourne Golf Club

- Metlink – Guide to transport in Melbourne

- A bird's eye view | Beaumaris Community- website of Beaumaris Community supported by the Community Bank