Matthew Webb

Captain Matthew Webb | |

|---|---|

Webb in The Illustrated London News, 1883 | |

| Born | 19 January 1848 Dawley, Shropshire, England |

| Died | 24 July 1883 (aged 35) Niagara River, Niagara Falls |

| Cause of death | Paralysis from water pressure leading to respiratory failure |

| Resting place | Oakwood Cemetery, Niagara Falls, New York |

| Monuments | Monuments and places |

| Occupation(s) | Seaman, swimmer, stuntsman |

| Years active | 1875–1883 |

| Known for | Swimming the English Channel |

| Spouse | Madeleine Kate Chaddock (married 1880–1883) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Stanhope Medal |

Captain Matthew Webb (19 January 1848 – 24 July 1883) was an English seaman, swimmer and stuntman who became the first person to swim the English Channel without the use of artificial aids. Webb increased the popularity of swimming in England.

Born in Dawley, Shropshire, Webb developed his swimming skills as a child while playing in the River Severn. At twelve, he began his career in the Merchant Navy after training at HMS Conway. After graduating, he began a three-year apprenticeship with the Rathbone Brothers of Liverpool, during which he sailed internationally across various trade routes to countries including China, India, Hong Kong, Singapore and Yemen.

After completing his second mate training in 1865, Webb worked for ten years aboard different ships and for multiple companies. He was recognised for two acts of bravery: in the Suez Canal, he freed the ship's propeller from an entangling rope by diving underwater and cutting it, and in the Atlantic Ocean, he jumped in to attempt to save a man who had fallen overboard while the ship was travelling at 14.5 kn (26.9 km/h; 16.7 mph). This latter act earned him the first Stanhope medal.

In 1875, on his second attempt, Webb gained fame by successfully swimming the English Channel from Dover, England, to Cap Gris-Nez, France. Public donations raised him £2,424 (about £290,000 today), and he started a career as a professional swimmer. Webb competed in several races, and performed stunts in England and America, including completing a 40-mile (64 km) swim from Gravesend to Woolwich along the Thames in 1877, swimming 74 miles (119 km) over six days to win a long-distance swimming race in 1879, and floating for 128.5 hours at the Boston Horticultural Hall in 1882. Webb's financial situation worsened, and in 1883 he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, leaving him bedridden for two months. Webb died later that year after being paralysed by the water pressure while attempting to swim down the rapids at Niagara Gorge, below Niagara Falls.

Early life

[edit]Webb was born on 19 January 1848 in Dawley, Shropshire. He was one of 13 children of the surgeon Dr Matthew Webb.[1][2][3] In 1849, when Webb was 14 months old, his family moved to Madeley, and then in 1856 to Coalbrookdale, where they lived near the River Severn.[1][4]

Webb's first memory involved the water.[5] After school he would go with friends to play in the Severn, so by the age of seven he could swim.[6] This was uncommon for the time, as swimming was not generally considered a pleasurable activity, but rather a medical treatment.[7] At eight, Webb and his older brother Thomas saved his younger brother Charles from drowning.[8] Webb enjoyed showing off in front of his friends and reading sea stories, with the book Old Jack by W. H. G. Kingston inspiring him to become a seaman.[9][3]

Career as a seaman

[edit]

In 1860, at twelve years old, Webb began training for the Merchant Navy aboard the HMS Conway training ship.[10] Initially homesick and disliking the harsh conditions,[11] Webb soon became popular on the Conway and earned the nickname "Chummy Webb".[12] The routine was regulated, but allowed time for play, and students studied both traditional subjects and nautical skills.[13] Webb rescued a student who had fallen overboard.[3] He impressed his peers by swimming for extended periods.[14][15]

Apprenticeship with the Rathbone Brothers

[edit]In 1862, Webb began a three-year apprenticeship on eastern cargo ships operated by the Rathbone Brothers of Liverpool. He trained to become a second mate, earning £30 (about £3,500 today) for his three years' work.[1][3][15] His first voyage was from Liverpool to Calcutta. The crew faced bad weather that terrified Webb.[16] Despite this, he excelled in the harsh conditions and was not prone to seasickness unlike the other new recruits. The ship then sailed to Hong Kong, Singapore, back to Calcutta and then back home. In Hong Kong, Webb fought off a mugging attempt until a policeman caused the assailants to flee.[17]

His next trip was to Aden and then Bombay, where he spent three months and first swam in the sea. He swam between the boats in the harbour, dining at his destination and swimming back again. He enjoyed the extra buoyancy that the saltwater provided, and the roughness of the waves.[18] Webb gained a reputation for fearlessness and was admired by his comrades.[14] After his third voyage, he passed his second mate qualification.[18]

Work as a second mate and seaman

[edit]Webb's contract expired in 1865, after which he became a second mate for Saunders & Co., another Liverpool-based shipping company. He worked on ships to Japan, Brazil and Egypt.[18]

Webb was confident in his physical abilities, especially in swimming. He would leap off the yardarm into the sea, and earned an extra £1 per day for anchoring near a wreck, and then swimming back to shore—a job which the other sailors were too afraid to do.[19] In one incident, he competed with a Newfoundland dog to see who could swim the longest in the rough sea. After an hour, Webb was still swimming but the dog had to be rescued from the water.[14][20] In the Suez Canal, his ship's propeller became tangled with a rope. Webb dived down repeatedly for hours, cutting the rope until the propeller was freed. Saunders & Co. never acknowledged his efforts so he left for the United States.[21]

Disliking the US, Webb took a job as an ordinary seaman on the Cunard Line ship Russia to return to the UK.[22] During the voyage, he attempted to rescue a man overboard by jumping into the cold mid-Atlantic Ocean while the ship was travelling at 14.5 kn (26.9 km/h; 16.7 mph).[3] During the 37 minutes before he was rescued, Webb nearly drowned.[23][3] The man was never found, but the passengers of the Russia gave Webb a purse of gold[24] and upon returning home, he learned that his attempted rescue had won him the first Stanhope Medal and made him a hero in the British press.[1][3]

From 1865 to 1875, Webb worked on seven ships, the last being the Emerald, where he served as captain for six months.[3][1]

English Channel swimming record

[edit]In mid-1872, Webb read an account of the failed attempt by J. B. Johnson to swim the English Channel, and became inspired to try.[25][26]

Channel training

[edit]In 1874 Webb sought financial backers for his Channel attempt and other long swims. He approached Robert Watson, owner of the Swimming, Rowing and Athletic Record and Swimming Notes and Record, for support.[27] Though Watson doubted Webb would attempt the channel, he advised him to wait until next summer for better weather. Webb agreed and moved to Dover to practice. Locals there nicknamed him the "Red Indian" as he would often come back from long swims with a red face.[28] Before returning to Watson's office on Fleet Street, he tested himself by swimming to the Varne Lightvessel and back again, a distance of 13 miles (21 km).[29]

Watson was surprised by Webb's return and introduced him to Fred Beckwith, a coach at Lambeth Baths in south London.[27][30] Watson and Beckwith arranged a secret trial of Webb, watching him swim breaststroke down the Thames from Westminster Bridge to Regent's Canal Dock. After an hour and 20 minutes, they "grew tired of watching his slow, methodical but perfect breaststroke" and concluded his trial.[31] For the rest of the 1874 swimming season, Webb trained daily at Lambeth Baths.[32] He became close friends with Beckwith and Watson.[33]

In June 1875 Webb left his job as captain of the Emerald to focus on swimming.[3][25] That same month, future American rival Paul Boyton paddled across the Channel in a survival suit.[34][35] Although Boyton used a suit, the public viewed them as rivals, forcing Webb to match the standards of endurance that Boyton set.[36] Webb called Boyton "an obvious fraud".[37]

On 3 July Beckwith organised a spectacle with Webb attempting a 20-mile (32 km) swim from Blackwall to Gravesend along the River Thames, which he finished in 4 hours and 52 minutes.[3][38] Although Webb gained media attention for the feat,[38] low public interest on the rainy day meant Beckwith lost money. As a result, Webb hired a new manager, Arthur Payne, sporting editor of The Standard.[31]

On 17 July Webb announced his attempt to swim the English Channel with a statement in Bell's Life and Land and Water:[39][40]

I am authorised by Captain Webb to announce his full determination to attempt the feat of swimming across the Channel... Beyond a paltry bet of £20 to £1 he has nothing to gain by success. Surely, under the circumstances, there are some lovers of sport who would gladly, in sporting language, "put him on so much to nothing". Should he by chance succeed, which is extremely improbable, it would be cruel that one who would undoubtedly have performed the greatest athletic feat on record should be a loser by the event.

— Arthur Payne

Webb's next swim was a 20-mile journey from Dover to Ramsgate. He hired a local boatman and invited a reporter from the Dover Chronicle.[41] Despite heavy rain, he set off just before 10:00 with the tide in his favour. Webb alternated between breaststroke and sidestroke,[42] finishing in eight hours and 40 minutes at Ramsgate Pier.[43] The only newspaper to report was the Dover Chronicle.[43]

After his long swims, Webb underwent a medical check in London, which was reported in the Land and Water.[44] An employee there gave Webb a jar of porpoise oil for insulation, which he later used for his Channel swim.[45]

In August Webb moved from London to the Flying Horse Inn in Dover to begin final preparations. He swam an hour daily, except every tenth day when he swam up to five hours.[46]

Channel swim

[edit]Webb consulted locals about conditions in the Strait of Dover and chose to use Boyton's strategy. He planned to start on the east flood tide and catch the current as it turned west.[47] For support, he chose the lugger boat Ann, which was captained by George Toms.[1][48] Webb did not want a doctor, since he believed he knew his health best.[49]

First attempt

[edit]

Webb waited for moderately good weather and began his first attempt on 12 August.[50][1] According to Dolphin from the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, during the swim, he tried an early form of goggles without a seal, which he called "barnacles", but they did not work.[51] The weather worsened, and after seven hours he was over nine miles off course.[25][52][53] He boarded the boat 15 minutes before the weather conditions would have prevented him doing so. Despite his disappointment, he remained positive and was assured by Toms that with better weather, he likely would have succeeded.[54]

Successful attempt

[edit]Good weather arrived on 24 August with a good barometer reading, light wind and slightly overcast sky. The sea temperature was 18 °C (64 °F).[55] Webb ate bacon and eggs with claret, then set off in the Ann from the Harbour to Admiralty Pier.[56] Toms predicted the swim would take around 14 hours, while Captain Pittock of the Castalia—who was an expert on the Channel waters—estimated it would take around 20.[55] At the time of his swim, Webb weighed 204 lb (93 kg), his chest size was 40.5 in (1,030 mm) and he was 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) tall.[35]

At 12:56 pm, Webb dived from the pier in his red silk swimming costume.[1] He set off into the ebb tide which carried him for the first three-quarters of a mile.[35][25][52] Webb was backed by the Ann and two smaller rowing boats operated by Charles Baker, who joined Webb in the water for parts of the swim, and John Graham Chambers.[56][58] Aboard the Ann were: Toms and his crew, Webb's brother-in-law George Ward, Payne (acting as a referee and reporter for the Land and Water and The Standard) and reporters from The Field, the Daily News, the Dover Express, The Daily Telegraph, the Dover Chronicle, The Times, the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News and The Illustrated London News.[56][1][52]

Webb started swimming breaststroke at 25 strokes per minute but soon slowed to 20. He consumed cod liver oil, beef tea, brandy, coffee and ale, but did not stop long for each feed to preserve body heat.[59][60]

By 17:30, Dover could not be seen. At 20:35, Webb was stung painfully by a jellyfish, but he continued after a shot of brandy, and by 23:00, Toms believed they were over halfway.[59][61] A mail boat named The Maid of Kent passed Webb, with passengers cheering.[62]

For five hours, the currents off Cap Gris-Nez prevented him from reaching the shore,[25] and he was visibly struggling.[63] By 21:30, Webb had slowed to twelve strokes per minute, and the crew grew anxious.[64] The Maid of Kent returned with a rowing boat containing eight people to shield Webb from the wind and rain,[65] and the crew sang the tune "Rule, Britannia!".[66]

After nearly 22 hours, at 10:41 am on 25 August, he landed near Calais.[35] His zig-zag course across the Channel covered about 39 miles (63 km).[35][67][1] After finishing, he fell into his friends' arms,[68] and slept in the Hotel de Paris.[69]

Reception

[edit]After his swim, Webb had a temperature of 38 °C (100 °F) and two long swellings on his neck. He slept almost continuously for 24 hours.[70] After meeting the crowds at the hotel and touring a lace factory,[71] Webb and George Ward boarded the flag-decorated Castalia for their return to England. Webb briefly went to the saloon but soon moved to the deck, where he was greeted by a cheering crowd.[72]

At Dover Harbour, a crowd eagerly awaited him. Webb, Toms and the crew boarded a carriage to the Flying Horse Inn.[73] Webb soon grew tired of the crowd and tried to leave for his home in Wellington via train. The crowd accompanied him to the train station, while the song "See the Conquering Hero Comes" was played.[74]

In Wellington, a crowd brought his carriage to Ironbridge, where the Mayor of Wenlock greeted him.[1] The journey was lit by candles, torches and lanterns held by the residents.[75] On Monday, he was met by a group from Dawley. They escorted him and his family down the High Street, where people welcomed him.[1][76] Flowers lined his route, and the day ended with a bonfire and fireworks.[77] When Webb visited the Baltic Exchange in London, workers stopped to cheer him.[78] He accepted invitations to visit the Lord Mayor of London, receive an ovation at the Royal Cambridge Music Hall and have his portrait drawn.[79]

Webb received gifts, including gold cuff links and collar studs, a gold watch and a North London Swimming Club gold cross.[80] The London Stock Exchange established him a testimonial fund, which raised him £2,424 (£290,000 today).[1][69][35] Webb gave £500 to his father and invested £1,782 before moving to Kensington, London.[35] For the rest of 1875, Webb spoke at boys' schools, including the Conway, where he was used as an example of English virtues.[81]

Several newspapers reported on Webb.[82] The Standard published Payne's account of the crossing,[83] and The Daily Telegraph interviewed Webb.[84] Surgeon Sir William Fergusson called Webb's feat "almost unrivalled as an instance of human prowess and endurance", and noted his body's likely ability for vasoconstriction to prevent heat loss.[35][85] It was suggested in parliament that Webb be knighted, with Richard Henry Horne being Webb's strongest advocate, but it never happened.[86]

It took 36 years for anyone else to swim the channel, accomplished by Thomas Burgess in 1911.[87] After Burgess completed the crossing, Webb's widow was interviewed. She was pleased that Burgess had succeeded, as it demonstrated the crossing was possible and would silence those who doubted Webb's achievement.[88] Since then, the channel has been crossed by over 2500 swimmers.[89]

Swimming career

[edit]After his record swim, Webb received recognition internationally and pursued a career as a professional swimmer.[61]

He began lecturing on his career and swimming-related topics,[90][91] where he opposed the common Victorian practice of forcefully dunking children, suggesting instead they learn by experimenting for themselves in shallow water.[92] He also licensed his name for merchandise, including commemorative pottery and matches.[91][61] Webb also wrote a book titled The Art of Swimming,[93] though this was mostly written by Payne.[94]

In August 1876, Webb accompanied Frederick Cavill on his first channel attempt, but it ended after Cavill drank a lot of whisky and was stung by jellyfish.[95] In Land and Water, Webb stated Cavill had only made it halfway, which angered him.[96] After Cavill's second attempt, he claimed to have finished nearly ten hours faster than Webb. This claim was quickly discredited when one of the witnesses was found to be fictitious. Cavill continued to taunt Webb for years.[97]

Early exhibition swims

[edit]Webb did not make much money, but lived a high-cost lifestyle and was generous.[98][91] In 1877, he bet £100 (about £12,000 today) at 20-to-1 odds that he could swim from Gravesend to Woolwich along the Thames. He completed the 40-mile swim which broke the record for the longest freshwater swim, and earned publicity from The Times.[99] The record stood until 1899 when it was beaten by Montague Holbein.[3]

By 1879, Webb was in financial trouble.[100] To raise funds, he entered a long-distance swimming race organised by Beckwith. The swimmers were tasked with swimming as far as possible over six days. The race was a moderate success for Beckwith, and Webb won the £70 prize.[101] He swam 74 miles (119 km), averaging 14 hours per day.[1]

Travel to America

[edit]Webb was attracting less attention, so in 1880 he went to America.[35][102] He found a new manager, Captain Henry Hartley, who arranged for The Manhattan Beach Company to wager $1,000 (about $30,000 today) on a ten-mile swim from Sandy Hook to Manhattan Beach. Webb was required to enter Manhattan Beach Harbour between 17:00 and 18:00 to ensure the largest possible audience.[103] Despite his crew's inexperience and Webb arriving three hours early, he finished the swim and fulfilled his contract.[104] The New York Times called the feat impressive but useless.[105]

On 22 August, Paul Boyton and Webb raced at Newport beach, each wagering $1,000, and James Bennett (Newport casino owner) added another $1,000 to the prize pool. Two white buoys were placed half a mile apart; Webb was tasked with swimming around them 20 times in regular trunks, while Boyton completed 25 laps in his suit. A large crowd gathered on the beach, and Boyton took an early lead. Webb suffered a cramp that ended his race, while Boyton paddled to the finish.[106]

Webb challenged Boyton to a rematch, which he accepted. The race took place at Nantasket Beach, and was promoted as the "Championship of the World".[35][107] Public interest was higher, with a prize pool of $4,000 (about $130,000 today). Boyton had to paddle between three buoys, and Webb between two. After several postponements, the race was held on 6 September. The details of the race are unclear, but the referee refused to declare a winner and later accused Webb of cheating by swimming to shore and running across the beach.[1][108] Webb denied the accusation, and it was revealed that the referee was Boyton's fiancée's father.[108] Boyton challenged Webb again in a letter to the New York Herald, offering greater odds, but Webb did not respond.[109]

Webb's next race was against Ernest Von Schoening, who defeated him in the "Endurance Championship of the World" on 14 September. Webb left the water after swimming 6 miles (9.7 km), and Hartley later said he had felt cramps coming on.[110]

Overall, Webb was unsuccessful in America and lost money on the trip.[111] On 27 April 1880, Webb and Madeleine Kate Chaddock married at St Andrew's Church, West Kensington, and they later had two children, Matthew and Helen.[1]

Deteriorating health

[edit]Webb's next endeavour was floating for 60 hours in the Royal Aquarium in Westminster.[112] Members of the public were distracted by other attractions, and few paid attention to him.[113] He followed this with a 74-hour float at Scarborough Aquarium,[111] which also received little public attention. In 1881, Webb's friend Frank Buckland from the Land and Water died, and Webb fell ill. Nevertheless, he continued swimming, participating in another six-day race at Lambeth Baths and a 16-mile (26 km) race against Willie Beckwith.[114]

Webb's health worsened when he raced Dr. G. A. Jennings at Hollingworth Lake. Although Webb had trained in the cold water, and was nearly twice as fast as Jennings, the 12 °C (54 °F) water caused him to hallucinate and become disorientated. With twelve minutes remaining, Webb lost his direction and with 30 seconds left, he climbed out of the water. He vomited and was assisted by Baker and Watson in returning to normal body temperature.[115]

He returned to America in 1882, where he won a 5-mile (8.0 km) race against railroad engineer George Wade at Brighton Beach, and another 5-mile race against 22 swimmers at Nantasket Beach. Both events were poorly organised and recognised as sporting events.[116] He floated for 128.5 hours (minus a 94-minute break) in Boston Horticultural Hall, attracting more attention than his previous floating exhibits in England;,[61][111] but his financial situation remained poor.[111]

Webb's last competitive swim was in March 1883, when he raced 20 miles (32 km) at Lambeth Baths against Willie Beckwith.[117] He withdrew from the race after coughing up blood due to tuberculosis.[111][118] By this time, Webb had lost 42 lb (19 kg) since swimming the Channel.[111]

For the next two months, Webb was bedridden. His brother, now Dr Thomas Webb, urged him to give up long-distance swimming for his health. Webb made one final public appearance to ceremonially start a race at Battersea Baths.[119]

Death

[edit]In 1882, Webb announced his intent to swim through the Whirlpool Rapids below Niagara Falls.[1] In June 1883, he and his family returned to America.[120] Fred Beckwith and Watson tried to dissuade him, with Watson later saying:[111][121]

As we stood face to face I compared the fine, handsome sailor, who first spoke to me about swimming at Falcon Court, with the broken-spirited and terribly altered appearance of the man who courted death in the whirlpool rapids of Niagara... let it be taken for granted that his object was not suicide, but money and imperishable fame.

— Robert Watson

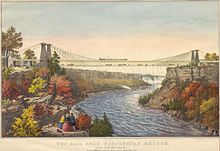

Webb rented a cottage and trained for a month at Nantasket Beach. He wrote a will leaving his property to his Madeleine.[122] He hired a new manager, Frederick Kyle, and travelled with him to Niagara on 23 July. The Niagara Falls Gazette announced Webb would start his swim at 16:00 that day.[123] Railway companies, charging visitors to watch, promised him earnings, which he estimated at $10,000.[124] The boat operator made a final attempt to dissuade him, but Webb only said "goodbye boy", before exiting the boat.[1]

The first part went smoothly, but upon being lifted by a large wave, Webb shouted and raised his arm, before being pulled underwater for about 130 ft (40 m). He briefly resurfaced several times, but was sucked into the whirlpool and never seen alive again.[1][125][126]

After Webb went missing, Kyle speculated he had likely ended up downstream, while others suggested suicide.[127] The next day at noon, Kyle sent Madeleine a telegram with the news, and at 22:00 he stopped the search for Webb alive, offering a $100 reward for Webb's body.[128][129] Rumours spread that Madeleine inherited a large sum, but Kyle told the public that Webb had left it to his children.[128]

Four days later, Webb's body was found. The autopsy revealed that he died from paralysis caused by water pressure, leading to respiratory failure.[1][130]

Webb was buried in Oakwood Cemetery.[131][132] Many of Webb's friends organised an ornamental swimming event at Lambeth Baths in his honour. The Land and Water criticized the risks Webb had taken later in life, and Bell's Life blamed the railway companies for his death.[133]

Webb's widow reburied Webb in Oakwood Cemetery with another funeral. A dark granite Gothic monument was placed above the grave, inscribed "Captain Matthew Webb. Born Jan. 19, 1848. Died July 24, 1883".[1][134]

Legacy

[edit]Webb wanted to inspire more people to learn to swim,[135] and The New York Times said he had had a positive impact by inspiring the country to swim.[136] In 1909, Webb's elder brother Thomas unveiled a memorial, funded by public donations, at the east end of Dawley High Street.[1] It bears the inscription: "Nothing great is easy."[137][61] Webb has another memorial in Dover and one at Coalbrookdale.[1][138][139] Webb Crescent and Captain Webb Primary School in Dawley are named after him,[140][87] as is Webb House of the Haberdashers' Adams Grammar School in Newport, Shropshire.[141] In 1965, Webb was added to the International Swimming Hall of Fame[93] for being the first person to cross the English Channel.[142]

His death inspired a poem by William McGonagall in 1883,[143] and John Betjeman's poem "A Shropshire Lad".[144][145] A film adaptation of Webb's Channel attempt, directed by Justin Hardy, written by Jemma Kennedy, and starring Warren Brown,[146] was released in 2015 under the title Captain Webb.[147]

See also

[edit]- List of members of the International Swimming Hall of Fame

- List of successful English Channel swimmers

- Gertrude Ederle – First woman to swim the English Channel

- Mercedes Gleitze – First British woman to swim the English Channel

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Peel, Malcolm. "Matthew Webb biography". Dawley Heritage Group. Archived from the original on 1 October 2024. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Seccombe 1899, p. 104.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 37.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 41.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c Sprawson 1993, p. 36.

- ^ a b Watson 2001, p. 47.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b c Watson 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 53.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 58.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 59.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 61.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d e "The daredevil channel swimmer". BBC Shropshire. 24 September 2014. Archived from the original on 19 July 2024. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 54–56.

- ^ a b Lambie 2010, p. 172.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Lambie 2010, p. 173.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Irving, Joseph (1879). "Captain Boyton". The Annals of Our Time from March 20, 1874, to the Occupation of Cyprus. London: Macmillan. p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Seccombe 1899, p. 105.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 86.

- ^ a b Watson 2001, p. 102.

- ^ Seccombe 1899, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 103.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 105.

- ^ a b Watson 2001, p. 106.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 106–108.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 109.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 110.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 111.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Dolphin 1875, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Lambie 2010, p. 174.

- ^ Sprawson 1993, p. 37.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 117.

- ^ a b Watson 2001, p. 118.

- ^ a b c Watson 2001, p. 119.

- ^ "Historic Framed Print, Admiralty Pier Dover England, 17-7/8" x 21-7/8"". Snapshots Of The Past. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ Bryant, M. A. "Chambers, John Graham". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5075. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Lambie 2010, p. 175.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 122–123.

- ^ a b c d e Mason, Paul (10 October 2013). "Heroes of swimming: Captain Matthew Webb". The Swimming Blog. The Guardian.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 127.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 128.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Sprawson 1993, p. 38.

- ^ "How The Channel First Was Swum. Captain Webb, Son of a Physician, Received Training as Sailor in China Trade. Killed in Niagara River. Tried to Cross Rapids in 1883 and Was Lost". The New York Times. 23 August 1925.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 133.

- ^ a b Lambie 2010, p. 176.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 139.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 141.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 145.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 149.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 151.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 152.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Lambie 2010, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 142–143.

- ^ "The Week". Br Med J. 2 (765): 282–283. 28 August 1875. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.765.282. ISSN 0007-1447.

- ^ Sprawson 1993, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b Watson 2001, p. 240.

- ^ "The Channel Swim". Poverty Bay Herald. Vol. XXXVIII, no. 12581. 11 October 1911. p. 8. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ "Channel Swimming & Piloting Federation - Solo Swims Statistics". Channel Swimming and Piloting Federation. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b c Sprawson 1993, p. 39.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 25.

- ^ a b "Captain Matthew Webb - Swim England Hall of Fame". Swim England. 30 September 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 170, 176.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 166.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 171.

- ^ Lambie 2010, pp. 176–178.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 172–175.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 175.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 179–182.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 178.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 182–186.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 188–189.

- ^ a b Watson 2001, pp. 189–191.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 191.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lambie 2010, p. 178.

- ^ Sprawson 1993, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 194–198.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 200.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 201–204.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 205.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 208.

- ^ Sprawson 1993, p. 40.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Sprawson 1993, p. 41.

- ^ Sprawson 1993, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 221, 217.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 218.

- ^ Sprawson 1993, p. 43.

- ^ "Captain Webb's Manager" (PDF). Boston Evening Traveller. 29 July 1883. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 223.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 224–227.

- ^ a b Watson 2001, p. 226.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 228.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 231–232.

- ^ "Captain Webb". The Globe and Mail. 1 August 1883.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 233–234.

- ^ Watson 2001, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 238.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 157.

- ^ Watson 2001, p. 137.

- ^ "Monument to Captain Matthew Webb (1848–1883)". National Recording Project. Public Monuments and Sculpture Association. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Sencicle, Lorraine (3 January 2015). "Captain Matthew Webb – the first Person to swim the Channel". The Dover Historian. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Shropshire's Captain Matthew Webb Named As Unsung Hero". Shropshire Tourism. 17 November 2009. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Haigh, Gerald (3 September 1999). "Names to live up to". Tes. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Daily News of Open Water Swimming (25 December 2013). "Landmarks, Monuments, Memorials of Open Water Swimmers".

- ^ "Captain Matthew Webb". ISHOF. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ Watson, Norman (2010). "Chronology of William McGonagall's Poems and Songs". Poet McGonagall: The Biography of William McGonagall. Edinburgh: Birlinn. pp. 289–299. ISBN 978-1841588841.

- ^ Wilde, Jon (15 February 2013). "Hidden treasures: Sir John Betjeman's Banana Blush". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "Why we love John Betjeman". The Guardian. 25 August 2006. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ "Brown: Portraying Webb an honour". BelfastTelegraph.co.uk. 12 December 2013. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "Warren Brown takes on his toughest ever job". Digital Spy. 14 August 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Watson, Kathy (2001). The crossing: the glorious tragedy of the first man to swim the English channel. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 1-58542-109-X.

- Sprawson, Charles (1993). Haunts of the Black Masseur: The Swimmer as Hero. London: Random House (published 17 June 1993). pp. 36–44. ISBN 978-0099223313.

- Lambie, James (2010). The Story of Your Life: A History of the Sporting Life Newspaper (1859–1998). Leicester: Matador. pp. 172–178. ISBN 9781848762916.

- Seccombe, Thomas (1899). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 60. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 104–105.

- Dolphin (1875). The Channel Feats of Captain Webb and Captain Boyton. London: Dean & Son.

Further reading

[edit]- Elderwick, David (1987). Captain Webb – Channel Swimmer. Redditch: Brewin. ISBN 0-947731-23-7.

- Webb, Matthew (1875). The Art of Swimming. London: Ward, Lock & Co.