Fitz James O'Brien

Fitz-James O'Brien | |

|---|---|

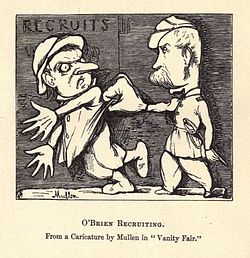

Sketch of Fitz-James O'Brien by William Winter 1881 | |

| Born | 25 October 1826 Cork, Ireland |

| Died | 6 April 1862 (aged 35) Cumberland, Maryland |

| Occupation | Writer, Poet, Soldier |

| Literary movement | Gothic fiction |

Fitz-James O'Brien (1826/8 – 1862) was an Irish-born American writer known for his pioneering works in fantasy and science fiction short stories. His career was marked by a significant contribution to the American literary scene in the mid-19th century. During the American Civil War, he enlisted in the Union Army and was mortally wounded in one of the early battles of the conflict.

Biography

[edit]Roots and Early Influences

[edit]Michael Fitz-James O’Brien (1826/8-1862) was born in County Cork, Ireland, with some debate over the exact date and year of his birth;[1] his first biographer, Francis Wolle, placed it between April and October of 1828.[2]: 3 His father, James O’Brien, was a local attorney of some influence, while his paternal grandparents, Michael O’Brien and Catherine Deasy, owned Brownstone House near Clonakilty. Fitz-James’s mother, Eliza O’Driscoll, was significantly younger than James at the time of their marriage. Her parents, Michael and Helen O’Driscoll, owned Baltimore House in County Limerick. After James’s death around 1839/40, Eliza remarried DeCourcy O’Grady, and the family moved to Limerick, where Fitz-James spent most of his teenage years.[2]: 3–5

O’Brien enjoyed a privileged upbringing, mastering activities like hunting, fishing, horseback riding, boating, and shooting. He also had a passionate fascination with birdwatching, which influenced his semi-autobiographical works and non-speculative fiction stories.[2]: 6 Thanks to his family’s considerable wealth, he was immersed in literature from a young age, with a profound interest in the works of the English Romantics. However, it was the American writer Edgar Allan Poe who left the most indelible mark on his formative years.

O’Brien’s earliest literary endeavors revealed a deep reverence for his homeland,[3] especially the geography of southwestern Ireland.[4] His first six poems were published in The Nation (Irish newspaper),[2]: 6–18 a weekly newspaper founded in 1842 to promote Irish nationalism, reflecting his early political convictions. Speculations about O’Brien’s whereabouts from March 1847 to July 1848 abound, with some suggesting he trained in law at Trinity College, Dublin, though no records confirm this. Others believe he might have served as a tutor in France, supported by his mastery of the French language and literature. His mother’s letter from October 1861 discussing the importance of a Continental tour in the O’Grady family tradition adds weight to this theory.[2]: 14–15

Early Career and London Adventures

[edit]In 1849, upon reaching adulthood, O’Brien inherited a substantial fortune estimated at around £8,000 from his father and maternal grandfather.[2]: 17 With this wealth, he journeyed to London, leaving behind his native land and family, never to see either again. Despite this physical separation, O’Brien maintained a deep connection to Ireland through his published writings.

O’Brien’s arrival in London marked a significant chapter in his life. His stepfather's well-established surname, O’Grady, opened doors to esteemed social circles. He immersed himself in the city's vibrant offerings, attending parties, theatrical performances, and making extravagant purchases of clothing and books. However, within two years, O’Brien had depleted his inheritance, prompting him to seek alternative means of sustenance. His passion for writing presented significant opportunities, having already published several pieces in The Family Friend (magazine), a London-based magazine founded in January 1849.[2]: 18–21 By the year's end, O’Brien achieved his first paid publication, marking a milestone in his burgeoning career.

In 1851, O’Brien’s career reached a pivotal turning point with the Great Exhibition in London. The event provided a platform to showcase technological advancements and support the burgeoning middle class.[5] Within the heart of this grand event, the Great Crystal Palace, O’Brien was appointed editor for The Parlour Magazine.[2]: 21 In this role, he undertook multiple responsibilities, including providing translations for French literary works and writing original pieces, all while serving as the chief editor. The fast-paced nature of this work within the central hub of the world fair consumed O’Brien’s time and energy but also provided him with valuable experience in honing his literary craft. In 1852, O’Brien suddenly departed from London for America, amid rumors of an affair with a married woman.[2]: 27–28 Seizing the opportunity, he swiftly boarded the first ship bound for America, equipped with scant funds but armed with remarkable letters of recommendation.

American Beginnings and Literary Connections

[edit]O’Brien’s inaugural year in America proved immensely fruitful. He quickly established vital connections, including a friendship with the Irish-American John Brougham, who launched the comedic publication The Lantern. O’Brien secured a position there, marking his debut in the American literary marketplace. He also bonded with Frank H. Bellew, an illustrator who brought O’Brien’s works to life in The Lantern and other publications throughout his career.[2]: 31–32

During the early 1850s, O’Brien formed deep and enduring friendships at Pfaff's Beer Hall, a hub for the New York Bohemians (who followed the lifestyle of Bohemianism), a group of intellectuals and artists. This circle, led by Henry Clapp, Jr., and featuring Ada Clare as its queen, included figures like Brougham and O’Brien, who assumed a princely role. The New York Bohemians comprised painters, sculptors, poets, actors, playwrights, novelists, storytellers, journalists, and critics, fostering an atmosphere of intellectual exchange and creative camaraderie.

O’Brien paid homage to the Bohemian movement in his story “The Bohemian” (1855),[2]: 92–107 published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (Harper's Magazine). While he often immersed himself in the Bohemian lifestyle, his writing only subtly reflected these experiences. His non-speculative fiction and poetry continued to address social issues, revealing a world fraught with danger and indifference, compelling characters to confront their surroundings with resilience and courage. Despite the anonymity of publishing in that era, which makes it challenging to ascertain the precise count of his contributions, O’Brien’s prolific output and profound impact on the literary landscape remained undeniable. In 1855, he published seven poems and ten stories, followed by six poems and eight stories in 1856, and eleven poems and four stories in 1857.

Ascendancy in Weird and Horror Fiction

[edit]The year 1858 marked a significant turning point in O’Brien’s literary journey as he delved into weird and horror fiction, just as the influence of Romanticism was waning. While he never reached the same mastery as Poe, O’Brien adeptly incorporated many of Poe’s techniques, showcasing his skill as a writer. His true contribution lies in infusing contemporary sensibilities into his narratives, setting tales of terror within commonplace settings. This approach allowed him to bridge tales of terror with emerging methods of modern Realism, foreshadowing the literary movements of Modernism and Postmodernism. O’Brien expanded the boundaries of the genre, serving as a crucial link between Romanticism and Realism.

One of his most notable achievements is “The Diamond Lens,” published in The Atlantic Monthly in January 1858.[2]: 151–157 This work exemplifies O’Brien’s ability to blend elements of the uncanny with a contemporary perspective. The narrative revolves around a mad scientist driven by an insatiable thirst for knowledge, a theme that recurs in O’Brien’s work. The pursuit of scientific enlightenment is tainted by the protagonist’s irrational desires and relentless quest for fame and fortune, leading him to morally questionable actions. The story, infused with philosophical undertones and moral introspection, prompts readers to contemplate fundamental questions about the human condition.[6]

In 1859, O’Brien solidified his literary prowess with two more stories: “What Was It? A Mystery” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine[2]: 171 and “The Wondersmith” in The Atlantic.[2]: 173 Both stories have become classics in horror and science fiction. “What Was It?” explores the concept of invisibility, while “The Wondersmith” is often regarded as the first story to explore robots. These narratives delve into profound philosophical territories, provoking contemplation on reality, ethics, and morality. O’Brien’s ability to intertwine philosophical depth with riveting storytelling cemented his status as a luminary of speculative fiction.

A Nation Divided and O’Brien’s Commitment

[edit]

In the turbulent 1850s, America was torn apart by internal strife, with slavery deepening the divide between the North and South. The nation teetered on the brink of Civil War, its unity threatened. At Pfaff’s Beer Hall, patrons viewed the impending conflict cynically, seeing it as a power struggle exploiting the common man for personal gain. Disillusioned, they believed neither the Democratic nor the Republican Party genuinely championed the nation's best interests, viewing the 1860 election as a mere shift in the privilege to plunder the country.

However, dissenting voices, including O’Brien’s, emerged. While some saw the war as a mere power struggle, O’Brien would find a deeper significance in the conflict. The attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, ignited Unionist fervor, resonating in New York. In response to President Lincoln’s call for support, New York mustered over thirteen thousand troops to safeguard the nation’s capital. A massive crowd of over one hundred thousand gathered at Union Square to bid farewell to the 7th New York Militia Regiment, composed of young merchants, bankers, professionals, and clerks, united in their determination to defend Washington.[2]: 232

O’Brien, recognizing the urgency, enlisted in the New York 7th Regiment, joining the defense of the capital. Inspired by a shared sense of purpose, he and his comrades prepared for the challenges ahead. Despite a warm welcome upon their return to New York on June 1, 1861, O’Brien’s spirit of service remained unwavering. He sought further opportunities to contribute, eventually joining General Lander’s staff in Virginia. Haunted by premonitions of his demise, O’Brien was deployed to Bloomery Gap, where he faced “Stonewall” Jackson’s cavalry. Wounded in battle, O’Brien endured a grueling journey for medical attention. Tragically, complications from an infection led to his death on April 6, 1862, leaving a legacy of courage and sacrifice.[2]: 232–251

His friend, William Winter, collected The Poems and Stories of Fitz James O'Brien, to which are added personal recollections by old associates that survived him.[7] Mr. Winter also wrote a chapter on O'Brien in his book Brown Heath and Blue Bells (New York, 1895). O'Brien was satirized as "Fitzgammon O'Bouncer" in William North's posthumously published novel The Slave of the Lamp (1855).[8]

Bibliography

[edit]Short Stories

[edit]- “An Arabian Night-mare” (Household Words, Nov. 8, 1851): A surreal tale that follows a merchant named Hamet, who experiences a fantastical and harrowing dream journey filled with jinn and supernatural encounters, reflecting themes of cultural dislocation and the mystical versus the rational.

- “A Legend of Barlagh Cave” (The Home Companion, Jan. 31, 1852): A tragic tale of fantasy that follows Aileen, a young maiden consumed by unrequited love, whose desperate quest for solace leads to a fatal encounter, highlighting the devastating effects of miscommunication and unfulfilled desire.

- “The Wonderful Adventures of Mr. Papplewick” (The Lantern, 1852): A science fiction story about a man who accidentally swallows a magnetic pill instead of a magnesium one, transforming himself into a human magnet and exploring themes of alienation and isolation that anticipate existentialist concerns.

- “The Old Boy” (The American Whig Review, Aug. 1852): A fantasy/science fiction story that follows Lionel Darkman, a young man who experiences an extensive and vivid dream in which he lives out the next ten years of his life, becoming a famous author. The dream is so realistic that when Lionel awakens and finds himself back in his teenage years, he struggles to reconcile his perceived future with his present reality. His knowledge of future events creates a sense of disorientation and difficulty in navigating his current life, as he grapples with the conflict between his dream and reality.

- “The Man Without a Shadow” (The Lantern, Sep. 4, 1852): A fantasy story of a man who discovers that a shadowy version of himself is following him. As he begins to interact with this shadow self, he finds that it only takes from him and causes torment. Eventually, the shadow disappears, leaving the man to reflect on the experience. The story is satirical and humorous, with self-referential and autobiographical elements, offering a playful yet poignant exploration of identity and self-perception.

- “A Voyage in My Bed” (The American Whig Review, Aug. 1852): A surreal fantasy story about an unnamed narrator who, struggling with insomnia, decides to take a nighttime walk. During his walk, he encounters an odd couple in a mysterious situation and attempts to intervene. However, he finds himself trapped by cobwebs sticking to his feet. As the scene unfolds, the characters suddenly turn to stone, and the narrator ultimately wakes up, realizing it was all a bizarre and vivid dream.

- “One Event” (The American Whig Review, Oct. 1852): A realistic story that follows John Vespar, who adopts a poor child named Annie as part of a twisted social engineering experiment to mold her into his ideal partner, ultimately intending to marry her. However, Annie falls in love with a local boy, Bolton Waller. Bolton reciprocates her feelings, but a mysterious circumstance forces him to leave, and he breaks up with Annie through a letter. Devastated, Annie kills herself in the freezing cold. John searches for her but finds her too late, frozen to death. Confronted with this tragedy, John resigns himself to a life of solitude, accepting that despite his intellectual pursuits, he is destined to be alone.

- “The King of Nodland and His Dwarf” (The American Whig Review, Dec. 1852): A political satire set on a fantasy island where the inhabitants spend most of their time sleeping. The island is ruled by a tyrannical king who imposes oppressive taxes on the people. The Nodlanders dominate a territory inhabited by the Cock-Crow Indians, whom they invade and enslave. The story serves as a critique of the political and social dynamics of America and England, using the fantastical elements to highlight issues of tyranny, exploitation, and colonialism.

- “A Peep Behind the Scenes” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Mar. 1854): A gothic tale about a young actor who loses his fiancée, serving as a parable about appreciating what and who you have in life. The title is a double entendre, offering insights into the world of theater while also reflecting on the ultimate stage—life itself. Through the protagonist's grief and reflections, the story underscores the importance of cherishing loved ones and the fleeting nature of existence.

- “The Bohemian” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Jul. 1855): A supernatural horror story featuring three characters: Henry Cranstoun, a lawyer desperate for wealth; Annie Deane, his fiancée with supernatural abilities; and Philip Brann, a bohemian mesmerist intent on hypnotizing Annie to discover the locations of lost treasures buried beneath New York. Cranstoun, despite Annie's hesitation, agrees to the plan. The hypnosis succeeds, but Annie falls gravely ill. Cranstoun and Brann leave to find the treasure, but when Cranstoun returns, he discovers that Annie has died in his absence. The story serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of pursuing wealth at all costs, highlighting the devastating consequences of greed and exploitation.

- “Duke Humphrey’s Dinner” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Aug. 1855): A poignant tale of tragedy and hope centered on Agnes Grey and Richard "Dick" Burdoon, both orphans with contrasting familial backgrounds. Agnes, from a wealthy family, falls in love with Dick, who has no relatives. Defying her family's wishes, Agnes marries Dick and is disinherited, leading the couple to a life of poverty. In one touching scene, they create an elaborate imaginary dinner, complete with a butler and chef, as a means of escaping their harsh reality. Caught up in their fantasy, they decide to sell their only valuable possession, a copy of Erasmus, to make ends meet. While out selling the book, Dick encounters Harry Waters, an old friend who is shocked by their impoverished state. Harry confronts the couple and convinces them to come live with him, offering them a glimmer of hope and a chance at a better life.

- “The Pot of Tulips” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Nov. 1855): A traditional ghost story featuring Harry Escott and Jasper Joye, who purchase a house from Harry's childhood, reputedly haunted by the ghosts of the Van Koerens, a wealthy Dutch family. Mr. Van Koeren was known to abuse his wife and child, Alain Van Koeren. Alain's daughter, Alice Van Koeren, is engaged to Harry, who buys the house to connect with her family history. After Mr. Van Koeren's death, his wealth goes missing, sparking numerous rumors. Harry and Jasper hope the house holds clues to the hidden fortune. One night, they encounter the ghosts of the Van Koerens, with Mr. Van Koeren holding a pot of tulips identical to one in their drawing room. This leads them to a hidden door in the house, revealing keys to the missing wealth. The story juxtaposes with "The Bohemian," as both feature characters seeking wealth to solidify their marriages. However, while one character in "The Bohemian" sacrifices his fiancée for wealth, Harry sacrifices for his fiancée and family, emphasizing themes of love and loyalty over greed.

- “The Dragon-Fang Possessed by the Conjuror Piou-Lu” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Mar. 1856):

- “The Hasheesh Eater” (Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, Sep. 1856)

- “A Terrible Night” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Oct. 1856)

- “The Mezzo-Matti” (Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, Nov. 1856)

- “The Crystal Bell” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Dec. 1856)

- “A Day Dream” (Harper’s Weekly, Feb. 21, 1857)

- “Broadway Bedeviled” (Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, Mar. 1857)

- “Uncle and Nephew” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Mar. 1857)

- “The Comet and I” (Harper’s Weekly, May 23, 1857)

- “My Wife’s Tempter” (Harper’s Weekly, Dec. 12, 1857)

- “The Diamond Lens” (The Atlantic Monthly, Jan. 1858)

- “From Hand to Mouth” (The New York Picayune, 1858)

- “The Golden Ingot” (The Knickerbocker, or New-York Monthly Magazine, Aug. 1858)

- “The Lost Room” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Sep. 1858)

- “Jubal, the Ringer” (The Knickerbocker, or New-York Monthly Magazine, Sep. 1858)

- “Three of a Trade; or, Red Little Kriss Kringle” (Saturday Press, Dec. 25, 1858)

- “What Was It? A Mystery” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Mar. 1859)

- “The Wondersmith” (The Atlantic Monthly, Oct. 1859)

- “Mother of Pearl” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Feb. 1860)

- “The Child That Loved a Grave” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Apr. 1861)

- “Tommatoo” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Aug. 1862)

- “How I Lost My Gravity” (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, May 1864)

Poetry

[edit]- "Oh! Give a Desert Life to Me" (The Nation, Dublin, Mar. 15, 1845)

- "Loch Ina, A Beautiful Salt-Water Lake, in the County of Cork" (The Nation, Dublin, Jul. 26, 1845)

- "The Famine" (The Nation, Dublin, Mar. 7, 1846)

- "Forest Thoughts" (The Cork Magazine, Dec. 1848)

- "The Lonely Oak" (The Parlour Magazine, Jul 12, 1851)

- "Madness" (The American Whig Review, Aug. 1852)

- "Pallida" (The American Whig Review, Sep. 1852)

- "The Song of the Immortal Gods" (The American Whig Review, Sep. 1852)

- "The Old Knight's Wassail" (The American Whig Review, Sep. 1852)

- "The Shadow by the Tree" (The American Whig Review, Oct. 1852)

- "Oinea" (The American Whig Review, Dec. 1852)

- "Sir Brasil's Falcon" (United States Magazine and Democratic Review, Sep. 1853)

- "The Heath" (The Evening Post, Oct. 19, 1855)

- "An Episode" (The Evening Post, May. 1, 1856)

- "The Ghosts" (The Knickerbocker, or New-York Monthly Review, Jan. 1859)

- "The Man at the Door" (The Knickerbocker, or New-York Monthly Review, Jan. 1861)

Essays

[edit]- "The Way to Get Burried" (The New York Daily Times, Mar. 19, 1853)

- "The Two Skulls" (Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Feb. 1853)

- "Bird Gossip" (Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Nov. 1855)

Collections

[edit]- Winter, William, ed. (1881). The Poems and Stories of Fitz James O'Brien. Boston: James R. Osgood and Co.

- ___. (1893). The Diamond Lens with Other Stories by Fitz-James O'Brien. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- O'Brien, Edward J., ed. (1925). Collected Stories by Fitz-James O'Brien. New York: Albert and Charles Boni.

- Seldes, Gilbert, ed. (1932). The Diamond Lens and Other Stories by Fitz-James O'Brien. Illustrations by Ferdinand Huszti Howath. New York: William Edwin Rudge.

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda, ed. (2008). The Wondersmith and Others. Ashcroft, British Columbia: Ash-Tree Press.

- Kime, Wayne R., ed. (2011). Behind the Curtain: Selected Fiction of Fitz-James O’Brien, 1853-1860. Newark: University of Delaware Press.

- ___. (2012) Thirteen Stories by Fitz-James O’Brien: The Realm of the Mind. Newark: University of Delaware Press.

- Irish, John P., ed. (2017). Fitz-James O'Brien: Gothic Short Stories. Texas.

- ___. (2018). Fitz-James O'Brien: Short Stories (1851-1855). (The Collected Writings of O'Brien, vol. 1). Texas.

- ___. (2018). Fitz-James O'Brien: Short Stories (1856-1864). (The Collected Writings of O'Brien, vol. 2).Texas.

- ___. (2018). Fitz-James O'Brien: Poetry & Music. (The Collected Writings of O'Brien, vol. 3).Texas.

- ___. (2018). The Best of Fitz-James O'Brien. (The Collected Writings of O'Brien, vol. 6).Texas.

- ___. (2025). The Lost Room and other Speculative Fiction. (Classics of Gothic Horror). New York: Hippocampus Press.

References

[edit]- ^ Everts, Randal A. "Michael Fitz-James O'Brien (1826–1862)". TheStrangeCompany.us.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Wolle, Francis (1944). Fitz-James O’Brien: A Literary Bohemian of The Eighteen-Fifties. University of Colorado.

- ^ Fanning, Charles (1999). The Irish Voice in America: 250 Years of Irish American Fiction. University Press of Kentucky. p. 87.

- ^ Irish, John P. "Ireland's Forgotten Poet: Fitz-James O'Brien's Writings in the Nation". SMU Pony Express(Ions) 2021 Edition.

- ^ Auerbach, Jeffrey A. (1999). The Great Exhibition of 1851: A Nation on Display. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 2.

- ^ Irish, John P. (2024). "Stories of Genius and Madness: Fitz-James O'Brien's Laboratories of the Mind". The Green Book (23): 33–44.

- ^ Winter, William (1881). The poems and stories of Fitz-James O'Brien. Boston: James R Osgood. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ "North, William (1825-1854) | The Vault at Pfaff's". pfaffs.web.lehigh.edu. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

Further Reading

[edit]- Anderson, Douglas A. “Questioning Attributions of Stories: Supposedly by Fitz-James O’Brien.” The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature. Issue 23 (2024): 22-32.

- Bleiler, Richard. “Fitz-James O’Brien (1828-1862).” The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature. Issue 18 (2021): 37-51.

- Chartier, Cecile. “An Inquiry into the Narrator's Psychological Conundrum in O'Brien's 'What Was It? A Mystery'” In Seeing the Unseen: Responses to Fitz-James O'Brien's 'What Was It? A Mystery', 109-118. Oxford: The Onslaught Press, 2014.

- Clareson, Thomas D. “Fitz-James O’Brien.” In Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror, Vol. 2, edited by E. F. Bleiler. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1985: 717-722.

- Corstorphine, Kevin. “Fitz-James O’Brien: The Seen and the Unseen.” The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature. Issue 5 (2015): 5-25.

- Dimeo, Steven. "Psychological Symbolism in Three Early Tales of Invisibility." In Riverside Quarterly 5, MLA-IB, 1977: 20-27.

- Fanning, Charles. The Irish Voice in America: 250 Years of Irish-American Fiction. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 2000.

- Fennell, Jack. “Mad Science and the Empire: Fitz-James O’Brien and Robert Cromie.” In Irish Science Fiction. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2014: 32-61.

- Huff, Joyce L. "The Domesticated Monster: Freakishness and Masculinity in Fitz-James O'Brien's 'What Was It?" Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies 4, no. 2, 2008.

- Irish, John P. “Fitz-James O’Brien Hands in His Chips: His New York Writings on Slavery and the Civil War.” New York History 103 (Summer 2022): 104-122.

- ___. “Ireland’s Forgotten Poet: Fitz-James O’Brien’s Writings in The Nation,” SMU Pony Express(Ions) 2021 Edition, August 17, 2020, https://smuponyexpressions.wordpress.com/2020/08/17/irelands-forgotten-poet-fitz-james-obriens-writings-in-the-nation/.

- ___. “‘Of Nobler Song Than Mine’: Social Justice in the Life, Times, and Writings of Fitz-James O’Brien” (2019). SMU Graduate Liberal Studies Theses and Dissertations. https://scholar.smu.edu/simmons_gls_etds/3

- ___. “Stories of Genius and Madness: Fitz-James O’Brien’s Laboratories of the Mind.” The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature. Issue 23 (2024): 33-44.

- Jouanne, Kristine Hoyt. “How Much of a Man is Three Fifths of a Man? Fitz-James O'Brien & the Dred Scott Decision.” In Seeing the Unseen: Responses to Fitz-James O'Brien's 'What Was It? A Mystery', 47-66. Oxford: The Onslaught Press, 2014.

- Levin,Joanna. Bohemia in America, 1858 – 1920. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2010.

- MacIntyre, Feargus Gwynplaine. “Seeing the Unseen: Creating a Biology and a Biome for Fitz-James O'Brien's Invisible Ghoul.” In Seeing the Unseen: Responses to Fitz-James O'Brien's 'What Was It? A Mystery', 69-95. Oxford: The Onslaught Press, 2014.

- Moskowitz, Sam. “The Fabulous Fantasist—Fitz-James O’Brien.” In Explorers of the Infinite: Shapers of Science Fiction. New York: World Publishing Co., 1963: 62-72.

- Orford, Pete. “Unfamiliar in their Mouths: The Possible Contributions of Fitz-James O’Brien to Household Words.” In Charles Dickens and the Mid-Victorian Press, 1850-1870, edited by Hazel Mackenzie and Ben Winyard, 211-231. Buckingham: University of Buckingham Press, 2013.

- ___. "What are they? The Pseudo-mystery stories of Fitz-James O'Brien." Clues: A Journal of Detection, 30:2, Autumn 2012: 10-18.

- Parry, Albert. Garrets and Pretenders: Bohemian Life in America from Poe to Kerouac. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 2012.

- Pattee, Fred Lewis. The Development of the American Short Story: An Historical Survey. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1923.

- ___. The Feminine Fifties. New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1940.

- Quinn, Arthur Hobson. "Some Phases of the Supernatural in American Literature." PMLA, Vol. 25, No. 1 (1910): 114-133.

- Riley, Joseph J. "A Keltic Poe." The Catholic World (March, 1920): 751-762.

- Satelmajer,Ingrid. "Publishing Pfaff’s: Henry Clapp and Poetry in the Saturday Press.” In Whitman among the Bohemians, edited by Joanna Levin & Edward Whitley. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2014.

- Staunton, Mathew D. “Not a Spook: A Personal Response to 'What Was It? A Mystery'” In Seeing the Unseen: Responses to Fitz-James O'Brien's 'What Was It? A Mystery', 135-165. Oxford: The Onslaught Press, 2014.

- Tauvry, Alexandra. “Invisibility in 'What Was It? A Mystery'” In Seeing the Unseen: Responses to Fitz-James O'Brien's 'What Was It? A Mystery', 121-132. Oxford: The Onslaught Press, 2014.

- Westfhal, Gary. "'The Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and Edgar Allan Poe Type of Story': Hugo Gernsback's History of Science Fiction." Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Nov., 1992): 340-353.

External links

[edit]- Works by Fitz James O'Brien at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Fitz James O'Brien at Internet Archive

- Works by Fitz James O'Brien at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "FitzJames O'Brien Bibliography". Violet Books. 10 February 1999. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012.

- "Summary Bibliography: Fitz-James O'Brien". The Internet Speculative Fiction Database. 24 April 2006.

- O'Brien, Fitz-James. "The Lost Room". ManyBooks.

- "O'Brien, Fitz-James (1826-1862)". The Vault at Pfaff's. 11 January 1922.

- Everts, Randal A. "Michael Fitz-James O'Brien (1826–1862)". TheStrangeCompany.us.

- American writers of Irish descent

- Irish science fiction writers

- Union Army officers

- 1826 births

- 1862 deaths

- Irish soldiers in the United States Army

- Irish male dramatists and playwrights

- Irish male poets

- American male dramatists and playwrights

- Irish journalists

- Irish male short story writers

- 19th-century Irish short story writers

- Irish emigrants to the United States

- People of New York (state) in the American Civil War

- Deaths from tetanus

- Union military personnel killed in the American Civil War

- Writers from New York (state)

- 19th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 19th-century American poets

- American male poets

- 19th-century journalists

- Male journalists

- 19th-century American short story writers

- 19th-century American male writers

- Weird fiction writers