Genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership in a group and aims at the destruction of a people.[3]

Genocide has occurred throughout human history, even during prehistoric times. It is particularly associated with the violence of European colonialism and with twentieth-century atrocities, particularly the Holocaust as its archetype.

Raphael Lemkin originally defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by means such as "the disintegration of [its] political and social institutions, of [its] culture, language, national feelings, religion, and [its] economic existence".[4] During the struggle to ratify the Genocide Convention, powerful countries restricted Lemkin's definition to exclude their own actions from being classified as genocide, ultimately limiting it to any of five "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group".[5]

The colloquial understanding of genocide is heavily influenced by the Holocaust as its archetype and is conceived as innocent victims targeted for their ethnic identity rather than for any political reason.[1] Genocide is widely considered to be the epitome of human evil and often referred to as the "crime of crimes", consequently, events are often denounced as genocide.

Origins

Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the term genocide between 1941 and 1943.[6][7] Lemkin's coinage combined the Greek word γένος (genos, "race, people") with the Latin suffix -caedo ("act of killing").[8][9] He submitted the manuscript for his book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe to the publisher in early 1942, and it was published in 1944 as the Holocaust was coming to light outside Europe.[6] Lemkin's proposal was more ambitious than simply outlawing this type of mass slaughter. He also thought that the law against genocide could promote more tolerant and pluralistic societies.[9]

According to Lemkin, the central definition of genocide was "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" in which its members were not targeted as individuals, but rather as members of the group. The objectives of genocide "would be the disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups".[4] These were not separate crimes but different aspects of the same genocidal process.[10] Lemkin's definition of nation was sufficiently broad to apply to nearly any type of human collectivity, even one based on a trivial characteristic.[11] He saw genocide as an inherently colonial process, and in his later writings analyzed what he described as the colonial genocides occurring within European overseas territories as well as the Soviet and Nazi empires.[9] Furthermore, his definition of genocidal acts, which was to replace the national pattern of the victim with that of the perpetrator, was much broader than the five types enumerated in the Genocide Convention.[9] Lemkin considered genocide to have occurred since the beginning of human history and dated the efforts to criminalize it to the Spanish critics of colonial excesses Francisco de Vitoria and Bartolomé de Las Casas.[12] The 1946 judgement against Arthur Greiser issued by a Polish court was the first legal verdict that mentioned the term, using Lemkin's original definition.[13]

Crime

Development

According to the legal instrument used to prosecute defeated German leaders at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, atrocity crimes were only prosecutable by international justice if they were committed as part of an illegal war of aggression. The powers prosecuting the trial were unwilling to restrict a government's actions against its own citizens.[15] In order to criminalize peacetime genocide, Lemkin brought his proposal to criminalize genocide to the newly established United Nations in 1946. He approached the African delegations first in an attempt to build a coalition of smaller states and former colonies that had themselves recently experienced genocide. Lemkin hoped that at this point the major powers—the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union—would step in and take credit for passing the convention.[15]

Opposition to the convention was greater than Lemkin expected due to various countries, and not just great powers, concerned that it would lead their own policies - including treatment of indigenous peoples, European colonialism, racial segregation in the United States, and Soviet nationalities policy - to be labeled genocide. Before the convention was passed, powerful countries (both Western powers and the Soviet Union) secured changes in an attempt to make the convention unenforceable and applicable to their geopolitical rivals' actions but not their own. The result gutted Lemkin's original intentions; he privately considered it a failure.[16] Over the course of these revisions, Lemkin's anti-colonial conception of genocide was transformed into one acceptable to colonial powers.[17] Among the violence freed from the stigma of genocide included the same actions targeting political groups, which the Soviet Union is particularly blamed for blocking.[18][19] Although Lemkin credited women's NGOs with securing the passage of the convention, the gendered violence of forced pregnancy, marriage, and divorce was left out.[20] Additionally omitted was forced migration of populations—which had been recently carried out by the Soviet Union and its satellites, condoned by the Western Allies, against millions of Germans from central and Eastern Europe.[21]

Genocide Convention

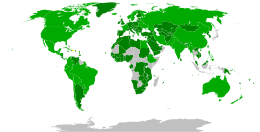

On 9 December 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG);[22] it came into effect on 12 January 1951 after 20 countries ratified it without reservations.[23] The convention's definition of genocide was adopted verbatim by the ad hoc international criminal tribunals and by the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court (ICC).[24] Genocide is defined as:

... any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- (a) Killing members of the group;

- (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.[5]

In addition, attempted genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, incitement to genocide, and complicity in genocide are criminalized.[25] The convention does not allow the retroactive prosecution of events that took place prior to 1951.[25] Many countries have incorporated genocide into their municipal law, varying to a lesser or greater extent from the convention.[26]

A specific "intent to destroy" is the mens rea requirement of genocide.[27] The issue of what it means to destroy a group "as such" and how to prove the required intent has been difficult for courts to resolve. The legal system has also struggled with how much of a group can be targeted before triggering the Genocide Convention.[28][29][30] The two main approaches to intent are the purposive approach, where the perpetrator specifically intends to commit genocide, and the knowledge-based approach, where the perpetrator understands that genocidal outcomes will result from his actions.[31] Perpetrators do not always make their intentions clear in public statements, although courts sometimes ascribe intent based on other factors.[32] Perpetrators often take advantage of the legal special intent requirement to claim that they merely sought the removal of the group from a given territory, instead of destruction as such,[33] or that the genocidal actions were collateral damage of military activity.[34]

Prosecutions

During the Cold War, genocide remained at the level of rhetoric because both superpowers (the United States and the Soviet Union) felt vulnerable to accusations of genocide, and were therefore unwilling to press charges against the other party.[35] Despite political pressure to charge "Soviet genocide", the United States government refused to ratify the convention fearing countercharges of racial segregation against African Americans.[36] The first conviction for genocide in an international court was in 1998 for a perpetrator of the Rwandan genocide. The first head of state to be convicted of genocide was in 2018 for the Cambodian genocide.[7]

Prosecutions for genocide do not obviously satisfy any of the purposes that criminal prosecution is supposed to serve. Retribution is impossible because any punishment proportionate to the crime would require collective punishment, which violates the principle of individual guilt.[37] The most plausible rationale for prosecuting genocide perpetrators is that it could prevent future genocides, but very few perpetrators are ever brought to trial and evidence of a deterrent effect is lacking.[38] However, genocide prosecutions might still serve the goal of upholding the power of international law.[39]

Genocide studies

The field of genocide studies emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, as social science began to consider the phenomenon of genocide.[40] Due to the occurrence of the Bosnian genocide, Rwandan genocide, and the Kosovo crisis, genocide studies exploded in the 1990s.[41] In contrast to earlier researchers who took for granted the idea that liberal and democratic societies were less likely to commit genocide, revisionists associated with the International Network of Genocide Scholars emphasized how Western ideas led to genocide.[42] Pioneers of research into settler colonialism such as Patrick Wolfe spelled out the genocidal logic of settler projects, prompting a rethinking of colonialism.[43]

Definitions

The definition of genocide generates controversy whenever a new case arises and debate erupts as to whether or not it qualifies as a genocide. Sociologist Martin Shaw writes, “Few ideas are as important in public debate, but in few cases are the meaning and scope of a key idea less clearly agreed.”[44] Some scholars and activists use the Genocide Convention definition.[17] Others prefer even narrower definitions that indicate genocide is rare in human history, reducing genocide to mass killing[45] or distinguishing it from other types of violence by the innocence[46] helplessness, or defencelessness of its victims, to distinguish it from warfare.[47] Some include political or social groups as potential victims of genocide.[48] Many of the more sociologically oriented definitions of genocide overlap that of the crime against humanity of extermination, which refers to large-scale killing or induced death as part of a systematic attack on a civilian population.[49] Isolated or short-lived phenomena that resemble genocide can be termed genocidal violence.[50]

Cultural genocide or ethnocide—actions targeted at the reproduction of a group's language, culture, or way of life[51]—was part of Raphael Lemkin's original concept, and its proponents in the 1940s argued that it, along with physical genocide, were two mechanisms aiming at the same goal: destruction of the targeted group. Because cultural genocide clearly applied to some colonial and assimilationist policies, several states with overseas colonies threatened to refuse to ratify the convention unless it was excluded.[52] Most genocide scholars believe that both cultural genocide and structural violence should be included in the definition of genocide, if committed with intent to destroy the targeted group.[53] Although included by Lemkin's original conception and some scholars, political groups were also excluded from the Genocide Convention. The result of this exclusion was that perpetrators of genocide could redefine their targets as being a political or military enemy, thus excluding them from consideration.[54]

Criticism of the concept of genocide and alternatives

Most civilian killings in the twentieth century were not from genocide, which only applies to select cases.[56][57] Alternative terms have been coined to describe processes left outside narrower definitions of genocide. Ethnic cleansing—the forced expulsion of a population from a given territory—has achieved widespread currency, although many scholars recognize that it frequently overlaps with genocide, even where Lemkin's definition is not used.[58] Other terms have proliferated, such as Rudolph Rummel's democide, for the killing of people by a government.[59] Words like ethnocide, gendercide, politicide, classicide, and urbicide were coined for the destruction of particular types of groupings (ethnic groups, genders, political groups, social classes, and a particular locality).[59][60]

Historian A. Dirk Moses argues that because of its position as the "crime of crimes", the concept of genocide "blinds us to other types of humanly caused civilian death, like bombing cities and the 'collateral damage' of missile and drone strikes, blockades, and sanctions".[61][62] Instead, Moses proposes to criminalize "permanent security" - an unobtainable goal of absolute security that if pursued, inevitably leads to anticipatory attacks that harm civilians.[63]

Prevention

Many scholars of genocide turned their attention to preventing genocide.[citation needed]

Responsibility to protect is a doctrine that emerged around 2000, in the aftermath of several genocides around the world, that seeks to balance state sovereignty with the need for international intervention to prevent genocide.[64] Yet, in practice it is primarily deployed by the United States and its allies when it is in their interest to criticize other less powerful countries, without affecting the immunity of powerful countries and their allies from legal liability for genocide.[65]

History

Lemkin applied the concept of genocide to a wide variety of events throughout human history. He and other scholars date the first genocides to prehistoric times.[66][67][12] Genocide is mentioned in various ancient sources including the Hebrew Bible, in which God commanded genocide (herem) against some of the Israelites' enemies, especially Amalek.[68][69] Genocide in the ancient world often consisted of the massacre of men and the enslavement or forced assimilation of women and children—often limited to a particular town or city rather than applied to a larger group.[70]

The destruction of indigenous societies as part of European colonialism was initially not recognized as a form of genocide.[71] Such genocides were often characterized by an initial violent struggle for land and resources on an imperial frontier which escalates to extermination. Later on, the survivors face ongoing genocide in the form of "a wide range of eliminatory practices such as cultural suppression, expulsion, segregation, child confiscation, assimilation, and of course, continued violence".[72] According to Mohamed Adhikari, the two main drivers of settler genocide is, in the long run, the pursuit of profit on the global commodity market and in the short run, indigenous resistance that triggered settler retaliation.[73] Economic activities such as mining, ranching, and agriculture prove so destructive to indigenous societies that the elimination of indigenous people is quicker when settlers are more integrated into global markets and have a higher expectation of profit.[74] While the lack of law enforcement on the frontier ensured impunity for settler violence, the closing of the frontier enabled settlers to consolidate their gains using the legal system.[75]

Genocide was committed on a large scale during both world wars. The prototypical genocide, the Holocaust, involved such large-scale logistics that it reinforced the impression that genocide was the result of civilization drifting off course and required both the "weapons and infrastructure of the modern state and the radical ambitions of the modern man".[76] Scientific racism and nationalism were common ideological drivers of many twentieth century genocides.[77]

Causes and perpetration

Although genocide is often conceived of as a large-scale hate crime motivated by racism instead of political reasons,[1] the Genocide Convention does not require any particular motive for the action. Motives for genocide have also included theft, land grabbing, and revenge.[5] Most genocides occur during wartime, and distinguishing genocide or genocidal war from non-genocidal warfare can be difficult.[78] Likewise, genocide is distinguished from violent and coercive forms of rule that aim to change behavior rather than destroy groups.[79][80] Although the organizer of genocide is often assumed to be a centralized totalitarian government, in many genocides paramilitaries and other decentralized perpetrators are involved.[81]

For genocide in the ancient and medieval world, longer-term causes included "ecological, demographic and agricultural crises".[82] A large proportion of genocides occurred under the course of imperial expansion and power consolidation.[83] Although genocide is typically organized around pre-existing identity boundaries, it has the outcome of strengthening them.[84]

Perpetrators of genocide have been under-studied despite the desire to understand how seemingly ordinary people can become involved in extraordinary violence.[85] Despite some studies of Holocaust perpetrators—particularly Christopher Browning's Ordinary Men, which concluded that fairly typical individuals could, under the right circumstances, agree to commit genocide—perpetrators of other genocides remained unexamined.[86] People who commit crimes during genocide often do not fit stereotypes of evil, nor recognize themselves as perpetrators.[87] While genocides may be carried out directly by state military forces,[citation needed] in other cases, such as during the Syrian civil war, state-sponsored atrocities are carried out by paramilitary groups that are offered impunity for their crimes. This offers the benefit of plausible deniability while widening complicity in the atrocities.[88] Although genocide perpetrators have often been assumed to be male, the role of women in perpetrating genocide—although they were historically excluded from leadership—has also been explored.[89]

Effects

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2024) |

Most of the qualitative research on genocide has focused on the testimonies of victims, survivors, and other eyewitnesses.[90]

Genocide recognition

The word genocide inherently carries a value judgement[91] as it is widely considered to be the epitome of human evil.[92] Although in a strict legal sense, genocide is not more severe than other atrocity crimes—crimes against humanity or war crimes—it is often perceived as the "crime of crimes" and grabs attention more effectively than other violations of international law.[93] Consequently, victims of atrocities often label their suffering genocide as an attempt to gain attention to their plight and attract foreign intervention.[94]

References

- ^ a b c Moses 2023, p. 19.

- ^ Shaw 2015, Conclusion of Chapter 4.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 11.

- ^ a b Bachman 2022, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Kiernan 2023, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 7.

- ^ a b Kiernan 2023, p. 2.

- ^ Lemkin 2008, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 14.

- ^ Shaw 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 15.

- ^ a b Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 11.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 20.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 22.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, p. 4.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 53.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 8.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, pp. 267–268, 283.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, p. 158.

- ^ Ozoráková 2022, p. 281.

- ^ a b Kiernan, Madley & Taylor 2023, p. 2.

- ^ Schabas 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Schabas 2010, pp. 136, 138.

- ^ Ozoráková 2022, pp. 292–295.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 13.

- ^ Schabas 2010, p. 136.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 35.

- ^ Kiernan, Madley & Taylor 2023, pp. 4, 9.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 57.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 47.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, p. 9.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, p. 266.

- ^ Bloxham & Pendas 2010, p. 632.

- ^ Bloxham & Pendas 2010, pp. 633–634.

- ^ Bloxham & Pendas 2010, p. 636.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, pp. 13, 17.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 9.

- ^ Shaw 2015, p. 38.

- ^ Shaw 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. ??.

- ^ Shaw 2015, Sociologists redefine genocide.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 3.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Shaw 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Bachman 2022, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 62.

- ^ Bachman 2021, p. 375.

- ^ Bachman 2022, pp. 45–46, 48–49, 53.

- ^ Moses 2023, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 25.

- ^ Graziosi & Sysyn 2022, p. 15.

- ^ Shaw 2015, Chapter 5.

- ^ a b Shaw 2015, Chapter 6.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 33.

- ^ Moses 2021, p. 1.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 118.

- ^ Moses 2023, pp. 16–17, 27.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 119.

- ^ Bachman 2022, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Naimark 2017, p. vii.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 31.

- ^ Naimark 2017, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, pp. 39, 50.

- ^ Kiernan, Madley & Taylor 2023, p. 6.

- ^ Adhikari 2023, p. 43.

- ^ Adhikari 2023, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Adhikari 2023, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Adhikari 2023, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 7.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 8.

- ^ Shaw 2014, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Shaw 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Kiernan, Madley & Taylor 2023, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Shaw 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 48.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 49.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 50.

- ^ Anderson & Jessee 2020, p. 3.

- ^ Anderson & Jessee 2020, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Anderson & Jessee 2020, p. 11.

- ^ Anderson & Jessee 2020, p. 12.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 10.

- ^ Anderson & Jessee 2020, p. 7.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Lang 2005, pp. 5–17.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 22.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 23.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Kjell; Jessee, Erin (2020). "Introduction". Researching Perpetrators of Genocide. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-32970-9.

- Bachman, Jeffrey S (2021). "Situating Contributions from Underrepresented Groups and Geographies within the Field of Genocide Studies". International Studies Perspectives. 22 (3): 361–382. doi:10.1093/isp/ekaa011.

- Bachman, Jeffrey S. (2022). The Politics of Genocide: From the Genocide Convention to the Responsibility to Protect. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-1-9788-2147-7.

- Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk, eds. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-161361-6.

- Bloxham, Donald; Pendas, Devin O. "Punishment as Prevention?". In Bloxham & Moses (2010), pp. 617–637.

- Schabas, William A. "The Law and Genocide". In Bloxham & Moses (2010), pp. 123–141.

- Graziosi, Andrea; Sysyn, Frank E. (2022). "Introduction: Genocide and Mass Categorical Violence". In Graziosi, Andrea; Sysyn, Frank E. (eds.). Genocide: The Power and Problems of a Concept. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-0-2280-0951-1.

- Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, T. M.; Taylor, Tristan S., eds. (2023). The Cambridge World History of Genocide: Volume 1, Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern Worlds. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-64034-3.

- Kiernan, Ben. "General Editor’s Introduction to the Series: Genocide: Its Causes, Components, Connections and Continuing Challenges". In Kiernan, Lemos & Taylor (2023), pp. 1–30.

- Lemos, T. M.; Taylor, Tristan S.; Kiernan, Ben. "Introduction to Volume I". In Kiernan, Lemos & Taylor (2023), pp. 31–56.

- Kiernan, Ben; Madley, Benjamin; Taylor, Rebe (2023). "Introduction to Volume ii". The Cambridge World History of Genocide: Volume 2: Genocide in the Indigenous, Early Modern and Imperial Worlds, from c.1535 to World War One. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-1-108-48643-9.

- Kiernan, Ben; Lower, Wendy; Naimark, Norman; Straus, Scott (2023). "Introduction to Volume III". The Cambridge World History of Genocide: Volume 3: Genocide in the Contemporary Era, 1914–2020. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-1-108-76711-8.

- Lang, Berel (2005). "The Evil in Genocide". Genocide and Human Rights: A Philosophical Guide. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 5–17. ISBN 978-0-230-55483-2.

- Lemkin, Raphael (2008). Axis rule in occupied Europe: laws of occupation, analysis of government, proposals for redress. Clark, New Jersey, USA: Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8.

- Moses, A. Dirk (2021). The Problems of Genocide: Permanent Security and the Language of Transgression. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-02832-5.

- Moses, A. Dirk (2023). "Genocide as a Category Mistake: Permanent Security and Mass Violence Against Civilians". Genocidal Violence: Concepts, Forms, Impact. De Gruyter. pp. 15–38. doi:10.1515/9783110781328-002. ISBN 978-3-11-078132-8.

- Naimark, Norman M. (2017). Genocide: A World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976527-0.

- Ozoráková, Lilla (2022). "The Road to Finding a Definition for the Crime of Genocide – the Importance of the Genocide Convention". The Law & Practice of International Courts and Tribunals. 21 (2): 278–301. doi:10.1163/15718034-12341475. ISSN 1569-1853.

- Rechtman, Richard (2021). Living in Death: Genocide and Its Functionaries. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-9788-7.

- Shaw, Martin (2014). Genocide and International Relations: Changing Patterns in the Transitions of the Late Modern World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11013-6.

- Shaw, Martin (2015). What is Genocide?. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7456-8710-0.

- Simon, David J.; Kahn, Leora, eds. (2023). Handbook of Genocide Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-80037-934-3.

- Adhikari, Mohamed. "Destroying to replace: reflections on motive forces behind civilian-driven violence in settler genocides of Indigenous peoples". In Simon & Kahn (2023), pp. 42–53.

- Irvin-Erickson, Douglas. "The history of Rapha'l Lemkin and the UN Genocide Convention". In Simon & Kahn (2023), pp. 7–26.

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (2017). The Soviet Union and the Gutting of the UN Genocide Convention. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-31290-9.